Race Is Often Used as Medical Shorthand for How Bodies Work. Some Doctors Want to Change That.

Several months ago, a lab technologist at Barnes-Jewish Hospital mixed the blood components of two people: Alphonso Harried, who needed a kidney, and Pat Holterman-Hommes, who hoped to give him one.

The goal was to see whether Harried’s body would instantly see Holterman-Hommes’ organ as a major threat and attack it before surgeons could finish a transplant. To do that, the technologist mixed in fluorescent tags that would glow if Harried’s immune defense forces would latch onto the donor’s cells in preparation for an attack. If, after a few hours, the machine found lots of glowing, it meant the kidney transplant would be doomed. It stayed dark: They were a match.

“I was floored,” said Harried.

Both recipient and donor were a little surprised. Harried is Black. Holterman-Hommes is white.

Could a white person donate a kidney to a Black person? Would race get in the way of their plans? Both families admitted those kinds of questions were flitting around in their heads, even though they know, deep down, that “it’s more about your blood type — and all of our blood is red,” as Holterman-Hommes put it.

Scientists widely agree that race is a social construct, yet it is often conflated with biology, leaving the impression that a person’s race governs how the body functions.

“It’s not just laypeople — it’s in the medical field as well. People often conflate race with biology,” said Dr. Marva Moxey-Mims, chief of pediatric nephrology at Children’s National Hospital in Washington, D.C.

She’s not talking just about kidney medicine. Race has been used as a shorthand for how people’s bodies work for years across many fields — not out of malice but because it was based on what was considered the best science available at the time. The science was not immune to the racialized culture it sprung from, which is now being seen in a new light. For example, U.S. pediatricians recently ditched a calculation that assumed Black children were less likely to get a urinary tract infection after new research found the risk had to do with a child’s history of fevers and past infections — not race. And obstetricians removed race and ethnicity from a calculation meant to gauge a patient’s ability to have a vaginal birth after a previous cesarean section, once they determined it was based on flawed science. Still, researchers say those race-based guidelines are just a slice of those being used to assess patients, and are largely based on the assumption that how a person looks or identifies reflects their genetic makeup.

Race does have its place during a doctor’s visit, however. Medical providers who give patients culturally competent care — the act of acknowledging a patient’s heritage, beliefs, and values during treatment — often see improved patient outcomes. Culturally competent doctors understand that overt racism and microaggressions can not only cause mental distress but also that racial trauma can make a person physically sick. Race is a useful tool for identifying population-level disparities, but experts now say it is not very useful in making decisions about how to treat an individual patient.

Because using race as a medical shorthand is at best imprecise and at worst harmful, a conversation is unfolding nationally among lawmakers, scientists, and doctors who say one of the best things patients can do is ask if — and how — their race is factored into their care.

Doctors and researchers in kidney care have been active recently in reevaluating their use of race-based medical guidance.

“History is being written right now that this is not the right thing to do and that the path forward is to use race responsibly and not to do it in the way that we’ve been doing in the past,” says Dr. Nwamaka Eneanya, a nephrologist with Fresenius Medical Care, who in a previous position with the University of Pennsylvania traced in the journal Nature the history of how race — a social construct— became embedded in medicine.

The perception that there is such a thing as a “Black” or “white” kidney quietly followed patient and donor as Harried and Holterman-Hommes were on the path to the transplant — in their medical records and in the screening tests recommended.

Medical records described Harried as a “47-year-old Black or African American male” and Holterman-Hommes as a “58-year-old, married Caucasian female.” Harried does not recall ever providing his race or speaking with his physicians about the influence of race on his care, but for two years or more his classification as “Black or African American” was a factor in the equations doctors used to estimate how well his kidneys were working. As previous KHN reporting lays out, that practice — distinguishing between “Black” and “non-Black” bodies — was the norm. In fall 2021, a national committee determined race has no place in estimating kidney function, a small but significant step in revising how race is considered.

Dr. Lisa McElroy, a surgeon who performs kidney transplants at Duke University, said the constant consideration of race “is the rule, not the exception, in medicine.”

“Medicine or health care is a little bit like art. It reflects the culture,” she said. “Race is a part of our culture, and it shows up all through it — and health care is no different.”

McElroy no longer mentions race in her patients’ notes, because it “really has no bearing on the clinical care plan or biology of disease.”

Still, such assumptions extend throughout health care. Some primary care doctors, for example, continue to hew to an assumption that Black patients cannot handle certain kinds of blood pressure medications, even while researchers have concluded those assumptions don’t make sense, distract doctors from considering factors more important than race — like whether the patient has access to nutritious food and stable housing — and could prevent patients from achieving better health by limiting their options.

Studying population-level patterns is important for identifying where disparities exist, but that doesn’t mean people’s bodies innately function differently — just as population-level disparities in pay do not indicate one gender is fundamentally more capable of hard work.

“If you see group differences … they’re usually driven by what we do to groups,” said Dr. Keith Norris, not by innate differences in those groups. Still, medicine often continues to use race as a crude catchall, said Norris, a UCLA nephrologist, “as if every Black person in America experiences the same amount and the same quantity of structural racism, individualized racism, internalized racism, and gene polymorphisms.”

In Harried and Holterman-Hommes’ case, one striking example of race being used as shorthand for determining how people’s bodies work was an informational guide given to Holterman-Hommes that said African Americans with high blood pressure could not donate an organ, but Caucasians with high blood pressure might still qualify.

“I can’t believe they actually wrote that down,” said Dr. Vanessa Grubbs, a nephrologist at the University of California-San Francisco. That worries Grubbs because using race as a reason to exclude donors can create a situation in which Black transplant recipients have to work harder to find a living donor than others would.

“I do think that criteria such as these become barriers for transplantation,” said Dr. Rajnish Mehrotra, head of nephrology at the University of Washington. He said that type of hypertension distinction could exclude potential donors — like the 56% of Black adults with high blood pressure in the U.S. — when more of them are sorely needed.

The inclusion of race did not necessarily affect Harried’s ability to receive a kidney, nor Holterman-Hommes’ ability to give him one. But following their case offers a glimpse into the ways race and biology are often cemented together.

The St. Louis Case

Harried and Holterman-Hommes met 20 years ago when they worked together at a nonprofit that serves youth experiencing homelessness in St. Louis. Harried was the guy who pulled kids out of their ruts and into a creative mindset, from which they would write poems and songs and do artwork. Holterman-Hommes said he was “the calm in their storm.” Harried calls Holterman-Hommes “big stuff” because she is the nonprofit’s CEO who keeps the lights on and the donations coming in. “You never knew that she was the president of the company,” said Harried. “There wasn’t an air about her.”

Harried resigned in 2018 as his health declined. Then in 2021, Holterman-Hommes saw a KHN article about Harried and decided to see if she could help her former colleague. Although Holterman-Hommes’ mother was born with one kidney, she had lived a long and healthy life, so Holterman-Hommes figured she could spare one of her own.

As Holterman-Hommes explored becoming a donor candidate, initial tests showed high blood pressure readings, in addition to lower-than-ideal kidney function. But “I like to get an A on a test,” she said, so she redid both sets of tests, repeating the kidney function test after staying better hydrated and the blood pressure test after a big work deadline had passed. She moved on in the screening process after her results improved.

Grubbs wonders whether, if Holterman-Hommes had been Black, “they would have just dismissed her.” Grubbs shared an instance in which she suspects that’s exactly what happened to the wife of a patient of hers in California who needed a kidney transplant.

The wife, who is Black and was in her 50s at the time, wasn’t allowed to give the patient a kidney because of her hypertension.

“There are people in this country that will tell you that, ‘Oh, white people donate kidneys, Black people don’t donate kidneys, and that’s not true,’” said Mehrotra. “You hear that racist trope. But [there are] all of these barriers to kidney donation.”

Barnes-Jewish Hospital later said it had given Holterman-Hommes an outdated guide, “an unfortunate circumstance that is being corrected,” and provided a new one that does not say Black people with hypertension cannot donate. Instead, it says that people cannot donate if they have hypertension that was either diagnosed before age 40 or requires more than one medication to manage.

But “at some point, it was a policy,” said Harried, whose kidneys have been failing for several years. And it’s unclear how many years that “outdated” guidance shaped perceptions among those seeking care at Barnes-Jewish, which performs more living-donor kidney transplants per year than any other location in Missouri, according to the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients.

There is little transparency into how medical centers incorporate race into their decision-making and care. Guidelines from the United Network for Organ Sharing, the national organization in charge of the transplant system, leave the door open for hospitals to “exclude a donor with any condition that, in the hospital’s medical judgment, causes the donor to be unsuitable for organ donation.”

Tanjala Purnell, an epidemiologist at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health studying disparities in kidney transplantation, said she knows of several centers that used race-based criteria, though some have relaxed those rules, instead deciding case by case. “There’s not a standard set to say, ‘Well, no, you can absolutely not have different rules for different people,’” she said. “We don’t have those safeguards.” Dr. Tarek Alhamad, medical director of the kidney program at the Washington University and Barnes-Jewish Transplant Center, said race-based criteria for kidney donations aren’t created to exclude Black people — it was born of a desire to avoid harming them.

“African Americans are more likely to have end-stage renal disease, they are more likely to have end-stage renal disease related to hypertension. And they are more likely to have genetic factors that would lead to kidney dysfunction,” said Alhamad.

Compared with white and Hispanic donors, non-Hispanic Black donors are known to be at higher risk for developing kidney failure because of their donation, though it’s still very rare.

He said it feels unethical to take a kidney from someone who may really need it down the line. “This is our role as physicians not to do harm.”

The Science

Researchers are studying a possible way to clarify who is really at risk in donating a kidney, by identifying specific risk factors rather than pinning odds on the vague concept of race.

Specifically, a gene called APOL1 could influence a person’s likelihood of developing kidney disease. All humans have two copies of this gene, but there are different versions, or variants, of it. Having two risk variants increases the chance of kidney injury.

The risk variants are most prevalent in people with recent African ancestry, a group that crosses racial and ethnic boundaries. About 13% of African Americans have the double whammy of two risk variants, said Dr. Barry Freedman, chief of nephrology at the Wake Forest School of Medicine. Even then, he said, their fate isn’t sealed — most people in that group won’t get kidney failure. “We think they need a second hit, like HIV infection, or lupus, or covid-19.”

Freedman is leading a study that looks, in part, at how kidney donors with those risk variants fare in the long term.

“This is really important because the hope is that kidneys won’t be discarded or turned down as frequently,” said Moxey-Mims, who is also involved in the research.

Researchers who are focused on health equity say that while APOL1 testing could help separate race from genetics, it could be a double-edged sword. Purnell pointed out that if APOL1 is misused — for example, if a transplant center makes a blanket rule that no one with two risk variants can donate, rather than using it as a starting point for shared decision-making, or if doctors offer the test based only on a patient’s looks — it could merely add another criterion to the list by which certain people are excluded.

“We have to do our due diligence,” said Purnell, to ensure that any effort to be protective doesn’t end up “making the pool of available donors for certain groups smaller and smaller and smaller.” Purnell, McElroy, and others steeped in transplant inequities say that as long as race — which is a cultural concept defining how someone identifies, or how they are perceived — is used as a stand-in for someone’s ancestry or genetics, the line between protecting and excluding people will remain fuzzy.

“That’s the heart of the matter here,” said McElroy.

So where does race belong in kidney transplant medicine? Many of the physicians interviewed for this article — many of them people of color — said it primarily serves as a potential indicator of hurdles patients may face, rather than as a marker of how their bodies function.

For example, McElroy said she might spend more time with Black patients building trust with them and their families, or talking about how important living donations can be, similar to the ways she might spend more time with a Spanish-speaking patient making sure they know how to access a translator, or with an elderly patient emphasizing how important physical activity is.

“The purpose is not to ignore the social determinants of health — of which race is one,” she said. “It’s to try to help them overcome the race-specific or ethnicity-specific barriers to receiving excellent care.”

While all the science gets sorted out, Eneanya is trying to get the message out to patients: “Just ask the question: ‘Is my race being used in my clinical care?’ And if it is, first of all, what race is in the chart? Is it affecting my care? And what are my options?”

“Just keep your eyes open, ask questions,” said Harried.

In late April, a kidney from Holterman-Hommes’ body was successfully placed into Harried’s. Both are home now and say they are doing well.

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.Subscribe to KHN's free Morning Briefing.

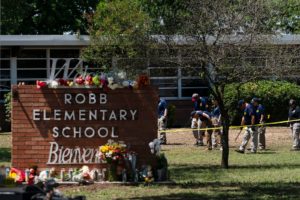

García-Siller has met with the husband of one of the teachers killed in the shooting. The archbishop also spoke with a person who called 911 to report the shooting and referenced a woman who drove children to the hospital from the school. “We don’t need heroes. We need just people of goodwill,” he said.

García-Siller has met with the husband of one of the teachers killed in the shooting. The archbishop also spoke with a person who called 911 to report the shooting and referenced a woman who drove children to the hospital from the school. “We don’t need heroes. We need just people of goodwill,” he said.