by Angelita Clifton | Dec 14, 2022 | Black History, Commentary, Headline News, Heritage |

(RNS) — Two months ago, I stood in Providence Baptist Church in Monrovia, Liberia, listening to the stories of Africans and Americans — the latter freed from slavery in the United States — who had banded together to establish the first republic on the continent of Africa two centuries before.

Providence, the oldest Baptist church in the West African country and the second oldest on the continent, was founded in 1822 by the Rev. Lott Carey, who had come as a missionary to the fledgling country and had brought a team of African American settlers home. Now, 200 years later, the Rev. Emmett L. Dunn, CEO of the Lott Carey Foreign Mission Convention, had brought a team of African Americans home.

I have traveled to several countries in Africa, and each one is imprinted on my heart in a special way. But hearing the stories of the African American settlers was cause to pause. I connected with the history of Liberia in a way I didn’t expect. I felt blessed beyond measure.

Landing in Liberia my spirit leaped like the baby in Elizabeth’s belly when greeting Mary, the mother of Jesus. The sights and sounds of Liberia greeted my senses, sending my head and my heart into overwhelming joy.

The Rev. Lott Carey. Photo courtesy of Creative Commons

In Liberia, I was at home. Home in the land of my ancestors on World Communion Sunday. Home, where a sense of “double consciousness” — a concept coined by W.E.B. DuBois to describe African Americans’ sense of dislocation from Africa and ourselves — liberated my thoughts and linked them to my theology in a free-spirited dance of deliverance.

It’s often said we must step back before we step forward. Walking in the footsteps of Lott Carey in the motherland afforded us the opportunity to do just that.

Born enslaved in 1780 in Charles City County, Virginia, Carey became a disciple of Jesus in 1807, purchased his freedom in 1813, and led the first Baptist missionaries to Africa from the United States in 1821.

After settling in Liberia, Carey and his pioneering missionary team engaged in evangelism, education and health care. He served as a missional and civic leader until his death in 1828.

Our pilgrimage relived aspects of this journey and the experiences of his team. We explored Providence Island, where Carey landed in Liberia in early 1822. Before we landed in Liberia, Dunn told us, “We expect that this journey into the past will bring home to us the love and sacrifice of those who walked this journey before us.”

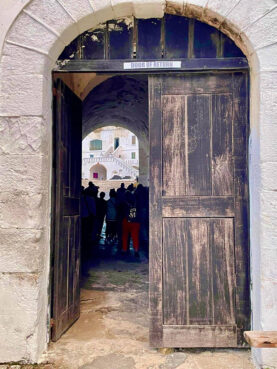

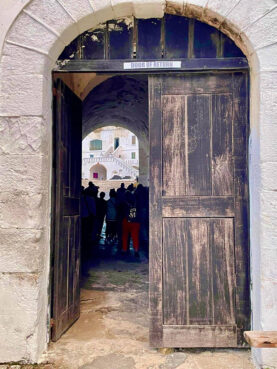

The Door of Return at the Slave Castle in Cape Coast, Ghana. It was once dubbed “The Door of No Return,” signaling the last time enslaved persons would see their homeland. Courtesy photo

Our next stop in Africa took us nearly 1,000 miles east along the coast of the Assin Manso Slave River and the Cape Coast castle in Ghana, unofficially dubbed “the Door of No Return” by our Ghanian sisters and brothers, through which so many of our ancestors were shackled and shipped into the slave trade in the New World. It has become a portal for African Americans, pulling us back to Ghana.

Before walking to the Slave River, where my ancestors received their first bath after being captured and their last bath before being carted off to the Americas, we held a ceremony of protection over Lott Carey’s life. In my sanctified imagination, my African ancestors’ prayers came to fruition in the proclamation made that day. What was meant for evil, God had used for good some 400 years later.

How ironic is it? In a whitewashed slave castle used to destroy the African spirit, a group of spirited African Americans reconnected with a long-lost history, historically whitewashed in American culture and the church universal.

My Bible says, “Be steadfast and persevering, my beloved sisters and brothers, fully engaged in the work of Jesus. You know that your work is not in vain when it is done in Jesus’ name.”

It was in that spirit that the last leg of our journey in homage to Lott Carey ended with saluting our ancestors on the same shores where they passed, returning where no return was promised. In the Twi language of Ghana, “sankofa” is a word meaning “go back and get it.” We did.

(The Rev. Angelita Clifton is president of Women in Service Everywhere and an associate minister at Fountain Baptist Church in Summit, New Jersey. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)

by Allen Reynolds, UrbanFaith Editor | Jan 19, 2022 | Commentary, Headline News |

(RNS) — On the day of a major voting rights debate on Capitol Hill, a social justice coordinator for the Progressive National Baptist Convention said fighting for voting rights is an effort to conquer evil.

“This convention practices a ministry of erosion,” said the Rev. Willie D. Francois III, co-chair of its social justice arm, during a Tuesday (Jan. 18) news conference held in Atlanta and livestreamed on the denomination’s social media.

“What does that mean? We keep showing up so that we wear evil down. The denial of voting rights is evil. The protection of Senate rules over the protection of the public is evil.”

The news conference was held at the historically Black denomination’s midwinter board meeting, just as legislators on Capitol Hill debated voting rights bills that the PNBC, along with a number of other faith organizations, support. However, the bills are not expected to pass.

Francois said the PNBC would be working with Faiths United to Save Democracy, a new coalition that has urged the Senate to change its rule about the filibuster, a stalling technique that requires 60 votes to end it and which is often used by the minority party to stop a bill from passing with a simple majority vote.

“The filibuster that was used to block anti-lynching laws cannot be used right now to block voter expansion,” Francois said. “And so we’re calling on our Senate to reform its filibuster to ensure that we can actually pass the John Lewis Voting Rights Act and we can also pass the Freedom to Vote Act.”

Regardless of what happens during the current debate, the PNBC leaders said they intend to move ahead with plans to lobby members of Congress in March and register voters weekly in their congregations and communities, aiming to increase voter rolls by 500,000.

The Rev. Adolphus Lacey, a pastor in New York’s Brooklyn borough, said these efforts will continue despite the ongoing coronavirus pandemic.

“COVID is real; COVID is a threat,” said Lacey, a PNBC social justice commissioner. “But even more serious than COVID, as real and scary as it is, is to see thousands and thousands of thousands of voters not being able to vote, and it was on our watch. We refuse to stop. We refuse to turn around.”

The denomination’s voter registration initiative will be aimed particularly at millennials and members of Gen Z.

But it will also focus on states with key races expected to have close margins, said the Rev. Darryl Gray of St. Louis.

“We don’t want to just register a half a million people,” said Gray, a PNBC pastor who served in the Kansas Senate in the 1980s and ran an unsuccessful 2020 campaign for Missouri state representative. “We want to register a half a million people in United States senatorial campaigns that are going to be consequential.”

PNBC leaders noted they belong to the denominational home of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., in a state at the center of voting rights debates. King co-pastored Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta and his Southern Christian Leadership Conference, which was influential in the civil rights movement, also is based in the city.

“We believe it is no coincidence that this convention, born out of the need to fight for justice, is in this state and city at such a time as this when our voting rights are under fierce attack,” said the Rev. David R. Peoples, president of the PNBC.

“This is a call to action from the Progressive National Baptist Convention. We come to not just pray. We come to not just push. We come to not just preserve. We’ve come to protect the right to vote.”

READ THIS STORY AT RELIGIONNEWS.COM

by Ben Finley, Associated Press | Oct 15, 2021 | Black History, Headline News, Heritage |

Jack Gary, Colonial Williamsburg’s director of archaeology, holds a one-cent coin from 1817 on Wednesday Oct. 6, 2021, in Williamsburg, Va. The coin helped archaeologists confirm that a recently unearthed brick-and-mortar foundation belonged to one of the oldest Black churches in the United States. (AP Photo/Ben Finley)

WILLIAMSBURG, Va. (AP) — The brick foundation of one of the nation’s oldest Black churches has been unearthed at Colonial Williamsburg, a living history museum in Virginia that continues to reckon with its past storytelling about the country’s origins and the role of Black Americans.

The First Baptist Church was formed in 1776 by free and enslaved Black people. They initially met secretly in fields and under trees in defiance of laws that prevented African Americans from congregating.

By 1818, the church had its first building in the former colonial capital. The 16-foot by 20-foot (5-meter by 6-meter) structure was destroyed by a tornado in 1834.

First Baptist’s second structure, built in 1856, stood there for a century. But an expanding Colonial Williamsburg bought the property in 1956 and turned it into a parking lot.

First Baptist Pastor Reginald F. Davis, whose church now stands elsewhere in Williamsburg, said the uncovering of the church’s first home is “a rediscovery of the humanity of a people.”

“This helps to erase the historical and social amnesia that has afflicted this country for so many years,” he said.

Colonial Williamsburg on Thursday announced that it had located the foundation after analyzing layers of soil and artifacts such as a one-cent coin.

For decades, Colonial Williamsburg had ignored the stories of colonial Black Americans. But in recent years, the museum has placed a growing emphasis on African-American history, while trying to attract more Black visitors.

Reginald F. Davis, from left, pastor of First Baptist Church in Williamsburg, Connie Matthews Harshaw, a member of First Baptist, and Jack Gary, Colonial Williamsburg’s director of archaeology, stand at the brick-and-mortar foundation of one the oldest Black churches in the U.S. on Wednesday, Oct. 6, 2021, in Williamsburg, Va. Colonial Williamsburg announced Thursday Oct. 7, that the foundation had been unearthed by archeologists. (AP Photo/Ben Finley)

The museum tells the story of Virginia’s 18th century capital and includes more than 400 restored or reconstructed buildings. More than half of the 2,000 people who lived in Williamsburg in the late 18th century were Black — and many were enslaved.

Sharing stories of residents of color is a relatively new phenomenon at Colonial Williamsburg. It wasn’t until 1979 when the museum began telling Black stories, and not until 2002 that it launched its American Indian Initiative.

First Baptist has been at the center of an initiative to reintroduce African Americans to the museum. For instance, Colonial Williamsburg’s historic conservation experts repaired the church’s long-silenced bell several years ago.

Congregants and museum archeologists are now plotting a way forward together on how best to excavate the site and to tell First Baptist’s story. The relationship is starkly different from the one in the mid-20th Century.

“Imagine being a child going to this church, and riding by and seeing a parking lot … where possibly people you knew and loved are buried,” said Connie Matthews Harshaw, a member of First Baptist. She is also board president of the Let Freedom Ring Foundation, which is aimed at preserving the church’s history.

Colonial Williamsburg had paid for the property where the church had sat until the mid-1950s, and covered the costs of First Baptist building a new church. But the museum failed to tell its story despite its rich colonial history.

“It’s a healing process … to see it being uncovered,” Harshaw said. “And the community has really come together around this. And I’m talking Black and white.”

The excavation began last year. So far, 25 graves have been located based on the discoloration of the soil in areas where a plot was dug, according to Jack Gary, Colonial Williamsburg’s director of archaeology.

Gary said some congregants have already expressed an interest in analyzing bones to get a better idea of the lives of the deceased and to discover familial connections. He said some graves appear to predate the building of the second church.

It’s unclear exactly when First Baptist’s first church was built. Some researchers have said it may already have been standing when it was offered to the congregation by Jesse Cole, a white man who owned the property at the time.

First Baptist is mentioned in tax records from 1818 for an adjacent property.

Gary said the original foundation was confirmed by analyzing layers of soil and artifacts found in them. They included an one-cent coin from 1817 and copper pins that held together clothing in the early 18th century.

Colonial Williamsburg and the congregation want to eventually reconstruct the church.

“We want to make sure that we’re telling the story in a way that’s appropriate and accurate — and that they approve of the way we’re telling that history,” Gary said.

Jody Lynn Allen, a history professor at the nearby College of William & Mary, said the excavation is part of a larger reckoning on race and slavery at historic sites across the world.

“It’s not that all of a sudden, magically, these primary sources are appearing,” Allen said. “They’ve been in the archives or in people’s basements or attics. But they weren’t seen as valuable.”

Allen, who is on the board of First Baptist’s Let Freedom Ring Foundation, said physical evidence like a church foundation can help people connect more strongly to the past.

“The fact that the church still exists — that it’s still thriving — that story needs to be told,” Allen said. “People need to understand that there was a great resilience in the African American community.”

by Adelle M. Banks, RNS | Jun 17, 2019 | Headline News |

SBC President J.D. Greear speaks on a panel discussion about racial reconciliation during the annual meeting of the Southern Baptist Convention at the BJCC, June 11, 2019 in Birmingham, Ala. RNS photo by Butch Dill.

At their annual meeting, Southern Baptists re-elected their president, adopted statements on their views about major cultural issues, and discussed how to deal with sexual abuse and racial discrimination in the church.

They also brought to center stage questions about church leadership roles that are appropriate for women in the church.

North Carolina pastor J.D. Greear, who was elected Tuesday (June 11) to a second one-year term as president, had emphasized a “Gospel Above All” theme for the meeting. He said that message was linked to multicultural worship music throughout the meeting and the inclusive approach Baptists took in appointing leaders to the convention’s various committees.

“We’re not where we need to be on those things, but I believe a signal has been sent that we believe that’s where we need to go,” he said at a news conference at the conclusion of the meeting on Wednesday.

“Now it’s on us to take the right steps at the right time and to move in a way that shows that it’s not words or virtue signaling but it’s something that we mean because we believe the Bible teaches it.”

Southern Baptist Theological Seminary President R. Albert Mohler Jr. said that in the past, issues of diversity were usually discussed mostly in hallways among small groups of church delegates, known as messengers. At this meeting, the conversations were held on the main stage of the gathering, which drew more than 8,000 messengers.

A Wednesday panel discussion on the value of women talked about whether a woman could be pastor (no, since the SBC’s doctrine limits that role to men) and whether a woman could one day become a president of the Southern Baptist Convention (maybe, since nothing in the SBC’s governing documents precludes women from that role).

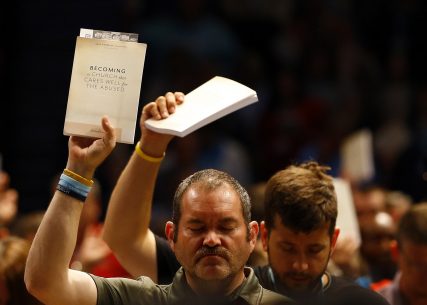

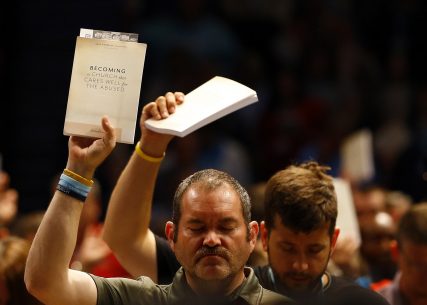

A messenger speaks to a motion during the annual meeting of the Southern Baptist Convention at the BJCC, June 12, 2019 in Birmingham, Ala. (RNS Photo/Butch Dill)

Panelists in a Tuesday discussion on racial reconciliation addressed how the issue affects both local congregations and the larger church. A pastor on the panel mentioned how a church member left his congregation when the congregant disagreed with the minister’s support of Baptists’ vote several years ago to repudiate the Confederate flag. Another mentioned how people of color are not likely to get to executive meeting rooms until they are in the same dining rooms with influential white leaders.

“It was definitely a different convention,” said Mohler. “There were more women’s voices and, by intentionality, more voices from African Americans and others who we very much want to be a part of the future of the Southern Baptist Convention.”

Pastor Dwight McKissic, a Texas minister who has advocated for more minorities and women to be placed in positions of leadership, agreed the issue of inclusion was highlighted at the meeting.

“It was clearly a move in that direction, stronger than I’ve ever seen, and I welcomed it and celebrate it,” he said.

Still, McKissic was concerned about a lack of diversity in the leadership of major Southern Baptist entities. He noted that the trustee chairman of New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary told messengers the search committee had considered several minority candidates when hiring a new president. But McKissic was disappointed that the board chair of the Executive Committee declined to be as forthcoming about details of its recent hiring process for a new president.

RELATED: Southern Baptist historic gavel a reminder of racist legacy

Abuse victim advocates noted the many actions Southern Baptists took on the abuse issue — including the introduction of “Caring Well” handbooks and video resources. But they still urged the convention to set up a database to help track abusers and keep them from moving from church to church.

Messengers hold up an SBC abuse handbook while taking a challenge to stop sexual abuse during the annual meeting of the Southern Baptist Convention at the BJCC, June 12, 2019, in Birmingham, Ala. RNS photo by Butch Dill

“A clergy database must be established, documenting confessed, convicted or credibly accused abusers,” said advocate Cheryl Summers at a rally she organized outside the Birmingham-Jefferson Convention Complex on Tuesday. “We have seen some progress, but there is a lot more work to be done.”

On Wednesday, Baptists also passed resolutions, nonbinding statements that give a sense of the views of those gathered for the annual meeting. They included:

- Urging the Supreme Court to overturn the 1973 Roe v. Wade decision that legalized abortion and celebrating “recent bipartisan gains in state legislatures that restrict abortion.”

- Calling the U.S. government to make religious liberty “a top priority of American foreign policy in its engagement with North Korea and China.”

- Recognizing critical race theory and intersectionality as “analytical tools” but repudiating their misuse.

- Urging the president and Congress to not include women in the Selective Service military registration, “which would be to act against the plain testimony of Scripture and nature.”

- Affirming their “commitment to Christ comes before commitment to any political party.”