by Jacob Lupfer, RNS | May 28, 2019 | Headline News |

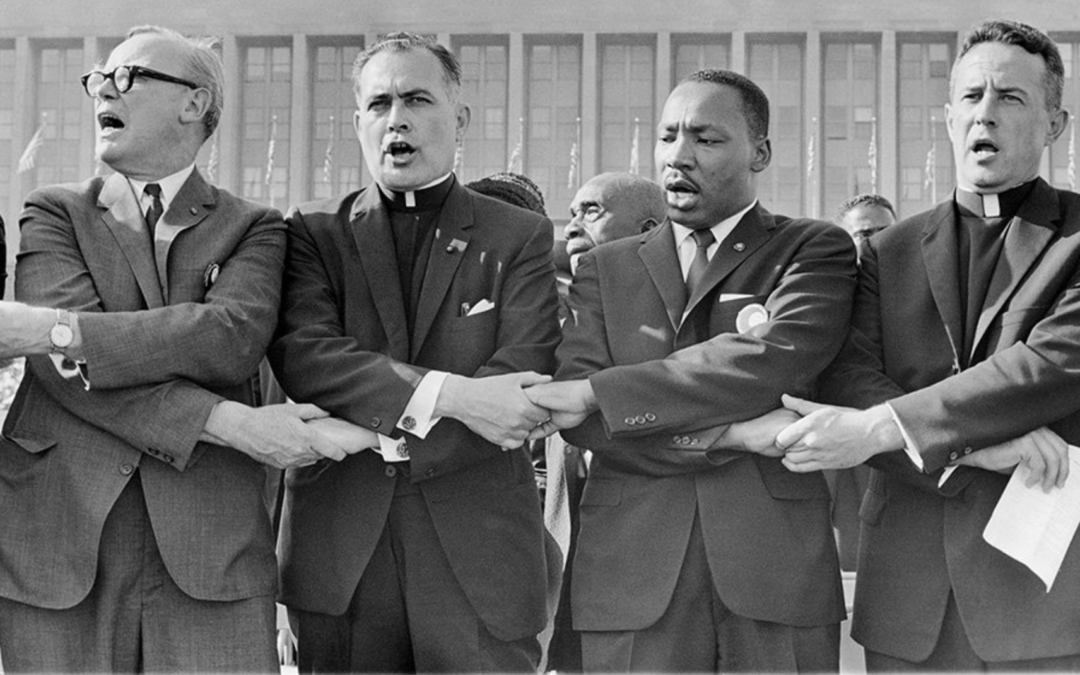

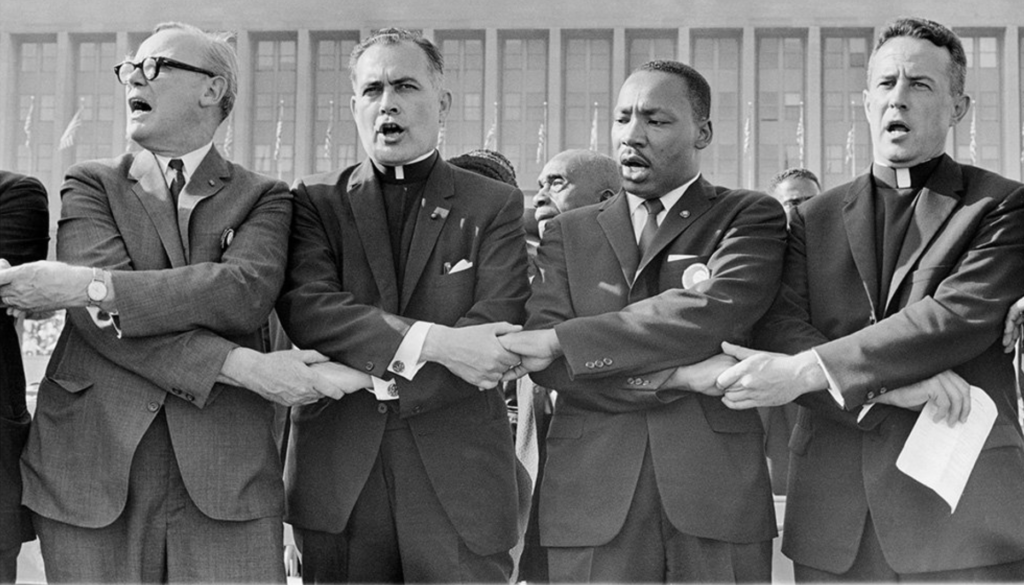

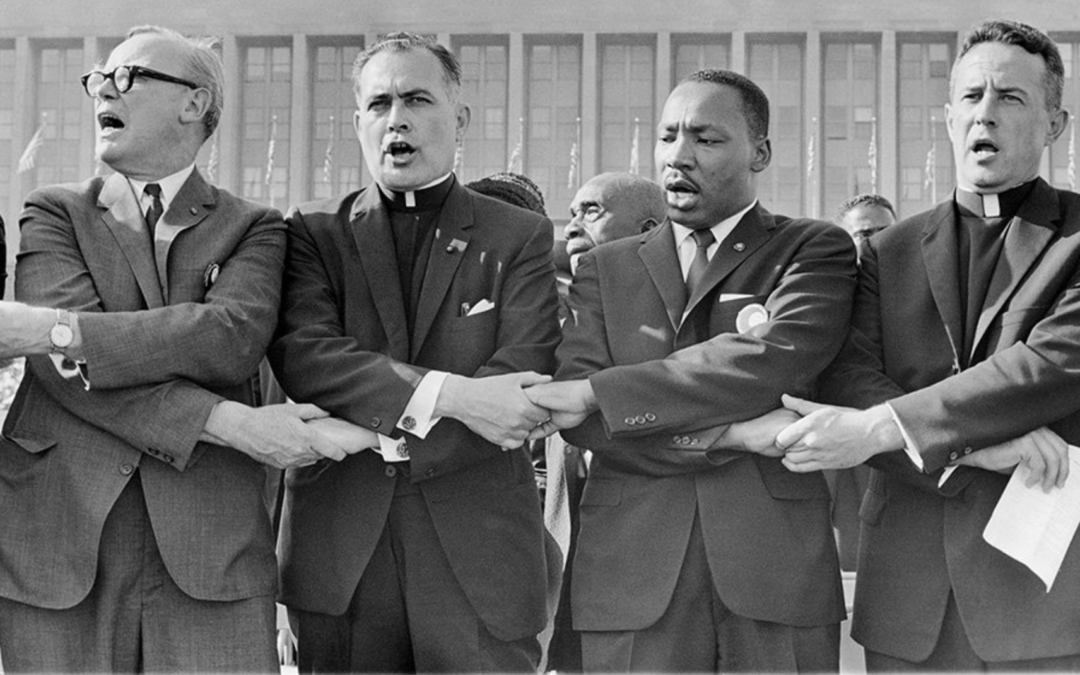

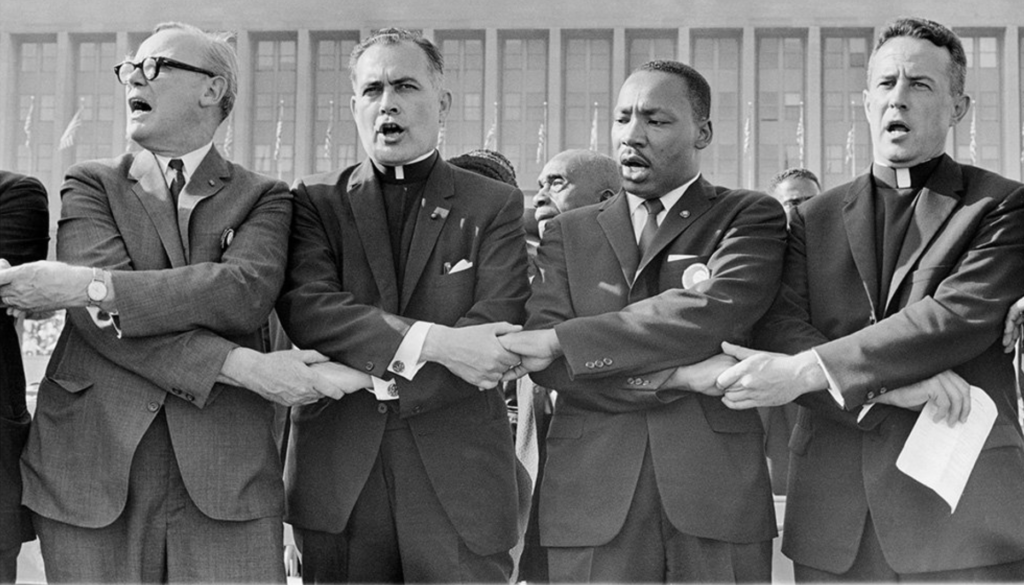

The Rev. Theodore Hesburgh, center left, holds hands with the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. while singing “We Shall Overcome” during a civil rights rally at Soldier Field in Chicago on June 21, 1964. Photo courtesy of OCP Media

In the media and in our popular imagination, the religious right towers over our political landscape. So much so, in fact, that one could be forgiven for thinking that reflexive Republicanism is the only widespread expression of Christianity in politics.

The religious right’s shadow is so large that it is usually the reference point for any discussion of the religious left. Each election cycle, a spate of articles, essays and columns, mostly by white journalists, appears, inquiring why the religious left is not as important as the religious right. Is there a religious left at all?

After their party largely neglected faith outreach in 2016, the 2020 Democratic presidential candidates seem to have caught the religion bug, and to hear them talk some might think the religious left has a chance this cycle to counter the religious right’s decades-long hold on American politics.

by UrbanFaith Staff | Jun 24, 2015 | Feature |

c. 2015 Religion News Service

(RNS) Inevitably, after the massacre at Emanuel AME Church, people are beginning to talk about arming congregants for self-defense. It is a sad image: 25 souls sitting around at Wednesday night prayer meeting, some packing heat in case the next church attacker should happen to be among them.

A mother and son stand at a makeshift memorial for victims of a mass shooting, outside the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, on June 22, 2015. Photo courtesy of REUTERS/Carlo Allegri

*Editors: This photo may only be republished with RNS-GUSHEE-COLUMN, originally transmitted on June 24, 2015.

Some people consider it a ridiculous idea, or dangerous, or even sacrilegious: Guns don’t belong in the house of the Lord Jesus, who taught turning the other cheek and peacemaking; guns don’t belong in the hands of angry people, and Lord knows people sometimes get real angry in church. Imagine an enraged deacon calling for a vote on whether to fire the pastor, gun in hand. (This might affect the church’s democratic process just a bit.)

Others have been in favor of guns in church for a long time. “Open carry” and/or “concealed carry” legislation has already been passed in numerous states, with application to numerous public places, including churches.

In Georgia last year, local church leaders found themselves on opposite sides of the issue, breaking down pretty neatly along left/right lines — yet another reminder that political ideology almost always seems stronger than shared Christian commitment in our red/blue culture. In the end, opponents managed to get an opt-in rather than opt-out system, so that churches would have to declare “guns welcome here” rather than having to declare the opposite. (An interesting addition to the run-of-the-mill messages on church signs.)

My most core Christian convictions center in the lordship of Jesus Christ, who laid down his life but did not take anyone’s life — and taught his followers the same pattern. When he could have defended himself, he did not. When the early church could have defended itself, it did not. Martyrdom and not defensive violence became the Christian paradigm. The early church dreamed of and worked for a renewed world and an end to its bloody violence.

But eventually Christians came to a theoretically limited embrace of violence, first in defense of the (supposedly Christian) Roman state and then its successors after the fourth century. Sometimes they embraced violence in the name of both state and church — for example, in suppressing heretics. Christians tended to support and participate in the violence governmental leaders ordered them to commit in criminal justice and in war, though just war/just violence theory set some limits — which gradually became refined over time.

Just-war thinkers always drew a sharp line between defensive and offensive violence, between justified and unjustified force. But just-war theory was primarily focused on the defense of the community or the state, not the individual Christian or the congregation. Romans 13:1-7 was read to authorize state violence as a deterrent, as defense, and as punishment of the wicked for violating communal peace and harming innocent people. But responsibility for executing that violence was left in the hands of government and its officials, which could and did include individual Christians but was separated from the function of the church. I could be shown to be wrong, but my reading of the Christian tradition is that the idea of heavily armed congregations hunkered down in self-defense in their houses of worship is a foreign concept.

But maybe that’s because for most of Christian history and in most places Christians did not need to feel afraid when they gathered in church. Excluding Muslim-Christian violence on those particular frontier lines — and after Christians in Europe and the colonies figured out how to stop killing each other over doctrinal differences — the average Christian didn’t need to be afraid of violence when she went to church.

This, of course, has not always been the case for the historic black churches in the United States, as Emanuel AME’s own history attests — though most white American Christians did not really notice before last week. As the center of African-American communal life, and often as the focal point of resistance to racist injustice, the black churches have periodically been victimized by violence. And yet I am not aware of any general pattern of African-American churches arming themselves in self-defense.

Perhaps that will change after last week. Certainly a general posture of open hospitality to the stranger could well be threatened.

I keep thinking about one stubborn fact of my own (limited) experience: I have never attended a Christian church that employed armed security, and I have never visited a Jewish synagogue that was not guarded by armed security. I first noticed it at a prosperous synagogue many years ago in northern Virginia, but since then have seen it elsewhere in the U.S. and abroad. I will never forget when my wife and I visited the historic Great Synagogue in Rome — where a 2-year-old boy had been murdered, and 34 children injured, in a horrific 1982 attack on a Shabbat service. A machine-gun-toting Italian police officer guarded that synagogue the day we were there. Armed security was certainly present in Jerusalem when I visited a synagogue in that city.

People regularly victimized by violence, including in their holy places, will seek to protect themselves. I cannot fault them for it. I fault those whose crimes have evoked this response.

Bottom line: Mosques, synagogues, churches and other holy places should not require armed security. But sometimes, in our wicked world, they face real threats to the unthreatening people praying there. State officials bear primary responsibility to protect those who are vulnerable. If they won’t or can’t do their job, it is terribly sad but not inappropriate for houses of worship to pay for the level of security required to keep their children and senior citizens from being murdered. This is preferable to the other solution — arming lightly trained or untrained civilians whose weapons probably risk doing far more harm than good.

May none of us ever stop yearning and working for the day when all this killing will end.

Copyright 2015 Religion News Service. All rights reserved. No part of this transmission may be reproduced without written permission.

by Dr. Vincent Bacote | Apr 10, 2012 | Feature, Headline News |

SEEKING HEALING: On March 31, congregants prayed for slain Florida teen Trayvon Martin and his shooter, George Zimmerman, during a service at the First Church of Seventh Day Adventists in Washington, D.C. The prayer was focused on racial healing and asked that people exercise patience to allow the judiciary to follow its course to bring about justice. (Photo: Nicholas Kamm/Newscom)

Many words have been and will be written about the death of Trayvon Martin, and the cocktail of grief, outrage, and confusion will likely linger long after the matter is resolved in one way or another. The circumstances of this unfortunate event have directed our attention to some of the challenges we face as a nation and as human beings, with considerable focus on the persistent difficulties connected to race. Whether or not Martin was racially profiled, this tragedy presents the opportunity to take paths that will lead us to better expressions of our humanity.

As director of Wheaton College’s Center for Applied Christian Ethics I had the privilege of participating in an event entitled “Civil War and Sacred Ground: Moral Reflections on War” (co-sponsored with The Raven Foundation). Two points raised at this thought-provoking conference can be helpful as we consider the long shadow of our history with race, particularly for followers of Christ. First, I continue to hear the echo of the following statement (paraphrased here) from Luke Harlow of Oakland University: “At the time of the Civil War, white supremacy was essentially held as an article of faith.” By this, he meant most citizens in the United States, North and South. Upon hearing this, I thought, No wonder it is so difficult for us to overcome the negative legacy of race.

The fact that racial superiority was so unquestioned suggests that the social, cultural, and political fabric of the Modern West in general and the United States in particular was constructed with a view of human beings that could be generalized as “whites” (or ethnic Europeans, who admittedly had their clashes) and “others.” Though the latter were identified according a range of racial categories, they definitely were not regarded as equal to “whites,” even among Christians. Of course there were those who did regard all humans as equal, but this was truly a minority report.

While many changes have occurred in the 150 years since the Civil War began, race consciousness remains in our social and cultural DNA like a stubborn mutation, rendering it difficult for us to truly and consistently regard “others” as equal before the eyes of God and fully human. This problem of otherness is not new, but it has manifested in a particularly malevolent fashion in the construction of racial identity. Today, this means that though great changes have occurred that would have been unimaginable 150 years ago, much more needs to change if we are to really live together as caring neighbors, at least in the church if not elsewhere. Yet this is an area where Christians continue to struggle, and many find themselves exhausted in reconciliation efforts.

The stubbornness of our race problem could lead us to despair, but taking a long view in light of where we have come from instead reminds us that we must have great patience as we pursue fundamental change. This patience is not the twin of apathy, but the disposition of steadiness and faithfulness in the face of at times imperceptible transformation. Change has occurred and can occur again.

Second, and more briefly, Dr. Tracy McKenzie, chair of Wheaton College’s history department, urged us to consider the difference between moral judgment and moral reflection. Whether it is the views held by most citizens 150 years ago or today in moments of racial conflict, moral judgment is the easy path which leads us to say “I can’t believe they held/hold such views and did such things.” Moral judgment keeps us separate from those we find reprehensible or disappointing. With moral reflection, while we may be surprised, disappointed, or offended by the ideas and actions we see in others, we are also prompted to consider our own moral architecture. In the question of race and otherness, moral reflection helps us to ask: What would I have thought if I were living at that time; how do I think about those that I readily regard as “other” from me; and does someone’s “otherness” make it easier for me to conclude that they are deficient in their humanness in some way and thus make it easier for me to disregard Christ’s command to love my neighbor as myself?

Moral reflection does not refuse to identify moral failings, but it leads us to look for them in places we might not peer otherwise. Moral reflection can prompt us to look at ourselves, our church, and our world in a way that brings us to a place of repentance that leads to transformation of life and even society.

Steady, faithful patience and moral reflection hardly exhaust our strategies for changing how we honor God in addressing the problem of race, but I find them helpful. What helps you?

This essay was adapted from an article at The Christian Post and was used by permission.

by Christine A. Scheller | Nov 10, 2011 | Feature, Headline News |

What if it wasn’t rape?

FALLEN LEGEND: Former Penn State football coach Joe Paterno was fired after failing to take more decisive action away from the field.

Amidst all the horrific stories in the grand jury report about retired Penn State assistant football coach Jerry Sandusky’s alleged sexual assaults on boys he met through his Second Mile charity is the somewhat less sensational story of “Victim 6.”

This boy was 11 years old in 1998 when Sandusky picked him up at his home, rubbed his thigh en route to Penn State, briefly worked out with him (but not hard enough for the boy to break a sweat), and then insisted they shower together.

“While in the shower, Sandusky approached the boy, grabbed him around the waist and said, ‘I’m going to squeeze your guts out.’ Sandusky lathered up the boy, soaping his back because, he said, the boy would not be able to reach it. Sandusky bear-hugged the boy from behind, holding the boy’s back against his chest. Then he picked him up and put him under the showerhead to rinse soap out of his hair,” the report says.

What if it was your child?

The boy testified that the incident felt “very awkward.” When he went home with wet hair, his mother questioned him about it, reported what happened to Penn State police, and later confronted Sandusky with a university police officer listening in the next room. Sandusky confessed to the disturbing and suspicious behavior, but there was no arrest.

I pull this story out from the more vile ones in the report because it illustrates what kind of behavior and outcomes most mandatory reporters face, and because it’s important to highlight the fact that it mattered a whole lot that one mother stood up to Sandusky and Penn State, thereby establishing an initial record of an alleged sexual predator’s deviant behavior.

What if it was your best friend?

At The Washington Post, columnist Sally Jenkins provocatively asks readers to forgive Sandusky’s boss, coaching legend Joe Paterno, for not reporting his assistant to police, because, she reasons, Paterno’s friendship with Sandusky blinded him. A friendship that close probably would have blinded you too, she implies.

As former FBI agent and pedophile profiler Ken Lanning tells her: “A hallmark of ‘acquaintance molesters’ is that they tend to be deeply trusted and even beloved. They are not strangers, but ‘one of us.’ They are expert at seducing children and are almost as expert at seducing adults, including parents, into believing in them.”

I’ve seen this happen. That it does isn’t an excuse for Paterno or anyone else who fails to act; it may just explain their initial self-deception. (Men’s Health editor Bill Philips suggests some other possible explanations here.)

What if it was your institution?

Amidst a bevy of posts on this story, American Conservative blogger Rod Dreher said the situation “causes us to reflect on the meaning of loyalty, and the meaning of courage.”

“Loyalty is only a virtue depending on the object of one’s loyalty. A mafioso is loyal, but his is a criminal loyalty,” he says. “The difficulty comes when one is asked to be loyal to a worthy cause or institution that is perpetuating or harboring evil.”

What if it was your culture?

Then Dreher turns the inquisitor’s lamp on himself and compares the Penn State situation to 1950s Jim Crow racism in the Deep South, where he grew up.

“I am seeing every day black people discriminated against, by law. Do I stand up against it? I am sorry to say that I am virtually certain that I would not. To have done so would have required going against … well, everybody in my own community.” But then Dreher imagines how he might’ve reacted had he witnessed a white man raping a black boy. “I think it almost certain that … I would have intervened, even violently,” he says, before confessing candidly: “But unless I was confronted directly with something that heinous, I probably would have euphemized and abstracted the evil away, because I couldn’t have faced my own moral responsibility.”

What if it wasn’t so blatant?

It’s easy to condemn a large, muscular man who doesn’t rip a rapist off a child, and other self-serving bystanders who fail to act. It’s much less clear what to do when the man’s behavior, like Sandusky’s thwarted attempt at “grooming” Victim 6, is wrapped in a fuzzy blanket of ambiguity, friendship, and good deeds.

What would you do?

Ask yourself: Would I have reported that?