by Maina Mwaura, Urban Faith Contributing Writer | Sep 28, 2022 | Commentary, Faith & Work, Headline News |

Val Demings describes herself as “a little rough around the edges.” She says what she thinks and cares more about serving people than political partisanship. She was raised by Christian parents, graduated from Florida State University, and stayed in her hometown of Orlando. She was a career police officer and then police chief who helped reduce crime by 40% in Orlando while she served as chief of police. But an invitation to run for congress changed her life and catapulted her onto the national stage. She is now running for US Senate in Florida.

Above is an UrbanFaith exclusive interview with US Congresswoman Representative Val Demings on how she got started in politics, how she maintains her faith as a public servant, and her hopes for a united future for our nation.

by Kathryn Post, RNS | Apr 21, 2022 | Commentary, Headline News, Social Justice |

(RNS) — Pastors in Grand Rapids, Michigan, are taking action as the city reels in the aftermath of the fatal shooting of 26-year-old Patrick Lyoya by a Grand Rapids police officer on April 4. Video footage of the shooting was released on Wednesday (April 13), sparking protests outside the city’s police department.

Lyoya, who is Black, was pulled over last week for a mismatched license plate. Video footage shows a white officer shooting Lyoya in the head after a brief scuffle. Lyoya and his family arrived from the Democratic Republic of the Congo in 2014 as refugees, and he leaves behind his parents, two young daughters and five siblings.

In the days since Lyoya’s death, a group of Black pastors in Grand Rapids, called the Black Clergy Coalition, has been organizing community events to promote dialogue, healing and justice.

“We think that our faith perspective is critical in this hour, to not just discuss policy change, which is necessary, but to also discuss the spiritual and faith dynamic,” said Pastor Jathan K. Austin of Bethel Empowerment Church in Grand Rapids. “We must continue to keep our trust in the Father so that people don’t lose trust in this time because of the heartache, the pain.”

On Sunday (April 10), the group helped organize a forum for community discussion in response to Lyoya’s death. The discussion took place at Renaissance Church of God in Christ in Grand Rapids — the location was intentional, according to the church’s senior pastor, Bishop Dennis J. McMurray, who noted the wider church’s historic role in guiding civil rights movements and said the Black Clergy Coalition is drawing on that legacy.

“It was unreal, the level of cooperative dialogue and understanding that took place,” McMurray told Religion News Service. “If these conversations would have started almost anywhere else, the volatility that could be associated to something as devastating as what we’re facing could have been a bomb that goes off that would cause so many other issues.”

The group also helped host a Thursday press conference at the Renaissance Church of God in Christ and a noon Good Friday service at the church, where they took up a collection for the Lyoya family.

The Rev. Khary Bridgewater, who lives in Grand Rapids, said the city’s racial and religious landscape informs how local leaders are responding to Lyoya’s death. Grand Rapids has a population that’s over 65% white and about 18% Black. It’s also the headquarters for the Christian Reformed Church, a small, historically Dutch Reformed denomination, and is home to over 40 CRC churches. According to Bridgewater, leaders shaped by the CRC’s reformed theology are often more likely to advocate for change within existing systems.

According to Bridgewater, “It’s very hard for most CRC churches to look at a system and say, ‘This is wrong, we’re going to act as activists to push the system into a different state.’ They’re more inclined to say, ‘Hey, let’s sit down and have a conversation with the leaders and try to do things differently.’” Bridgewater says this theology can bump up against the Black church’s prophetic tradition of change-making. For this reason, he said, Christian groups in Grand Rapids need to have theological discussions around topics like justice and citizenship.

Nik Smith, a Grand Rapids activist and member of Defund the GRPD, agrees the city’s religious culture is shaping local leaders’ responses.

“The nonprofits are run by Christian folk who are just waiting for Jesus to come, not realizing not only was he here already, but he’s given us things to live by,” said Smith. “So we have to be seeking justice actively in our community. We can’t just say, let’s pray. Prayer is not going to bring Patrick back.”

Smith has been involved in Defund the GRPD since 2020, when the coalition first began advocating for reducing the police budget and refunding over-policed communities. Though Smith doesn’t identify as a Christian as strongly as she once did, she believes the Bible highlights the consequences of earthly authorities wielding too much power and the importance of working to make the world a better place. For Smith, defunding the Grand Rapids Police Department is part of securing a better future.

For years, the city’s police department has been criticized for racial profiling and for drawing guns on Black children. Joseph D. Jones, who is a city commissioner and pastor, told Religion News Service he wants to address police and community relations by looking at “root causes” of socio-economic inequality and other disparities while also addressing training for officers.

“I do believe in the absolute power of prayer,” Jones added. “I’m asking those who do pray … to pray for the family of Patrick, to pray for our city, to pray that angels are encamped around our city to protect our city and to pray that God restore and change the hearts of those who desire to engage in anything that is seen as evil in our country and our world,” Jones said.

Austin of Bethel Empowerment Church said the Black Clergy Coalition has long been advocating for police reform and specifically wants to see better diversity and culture training for officers and changes in how the department responds to police shootings.

“I am going to allow the wheels of justice to roll, and we pray that they roll properly,” said McMurray, who is also part of the coalition. “We are working, but we’re also watching.”

READ THIS STORY AT RELIGIONNEWS.COM

by Jelani Greenidge, Urban Faith Contributing Writer | May 3, 2021 | Commentary, Headline News, Jelani Greenidge |

As another high-profile unjust killing fills the headlines across the nation, I can’t help but lament our current state of affairs – and the complicity the evangelical church shares with it.

Yes, the militarization of police is a problem. Yes, the police need better training. Yes, even though some police jurisdictions are using body cameras, there needs to be better civilian oversight regarding their deployment and the use of the resultant footage.

Nevertheless, there’s a connection between disproportionate uses of force (whether by police or civilians) against black people, and a fundamental misunderstanding of a popular passage of Scripture – Ephesians 6, where Paul describes “the armor of God.” As in many tragic illustrations of fallen humanity, the active toxic ingredient is fear.

Bad Experiences Can Generate Fear in the Hearts of God’s People

In the 2003 remake of The Italian Job, there’s a scene with Mos Def (now known as Yasiin Bey) as an explosives expert named Left Ear participating in a stakeout. Left Ear mentions that the person the team is surveilling has a dog on the premises. “I don’t do dogs,” he said. “I had a real bad experience.”

The team leader, played by Mark Wahlberg, chimes in. “What happened?” Left Ear claps back with a quickness.

“I HAD A BAD EXPERIENCE,” he says, stretching out the word ‘had’ for emphasis. It’s a funny moment because you can tell whatever that bad experience was, it left a significant mental scar, and he does not want to talk about it.

Unfortunately, this is the lens by which too many Christians view their engagement with the world around them. Maybe they were victims of crime, maybe they were made fun of for being a Christian at school or at work, maybe they experienced legitimate persecution for their faith, but whatever it was, they had a bad experience, okay?

These bad experiences often generate fear in the hearts of God’s people, and in an effort to avoid those them, sometimes we assume postures that are, let’s say, less than loving. We may get defensive and behave like everyone is a potential threat. (If you grew up in a household where no secular music or television was allowed, you know what I’m talking about.)

Or we may go on the offensive and behave as though it’s our job to eradicate the forces of evil around us. Any potential source of secular encroachment on our religious liberty, we treat like a national crisis. (If you’ve ever known anyone who thought about suing Starbucks because their cups read “happy holidays” instead of “Merry Christmas,” then you know what I’m talking about.)

Again, don’t forget … the operative word here is “fear.” It is fear of unbelieving, secular humanity – and the evil that can sometimes reside in the hearts of those who don’t know God – that drives people into these defensive or offensive stances.

Thus, when someone in this fear-driven mindset reads about the armor of God in Ephesians 6, they subconsciously go into full-on vigilante mode. Even if they don’t own any guns or weapons or whatever, because of how much our broader culture glorifies violence, they can’t help themselves. I mean, I grew up on action movies in the 80s, and I did this too. When I first was presented with teachings on what it means to “put on the full armor of God,” I had an image of Arnold Schwarzenegger gearing up for battle in the first Predator movie.

This is why we must read the Scriptures in context.

See, you can’t fully understand Ephesians 6:10-20 without first reading and taking in the other five chapters of Paul’s letter.

So, here’s an overview of those five chapters:

In Ephesians 1, Paul tells the Ephesians what an incredible, mysterious blessing of inheritance that they have in Christ. In Ephesians 2, he talks about how they were dead but became alive again, and because of this new life, the old ethnic categories that used to divide them would do so no longer.

In Ephesians 3, Paul explains that the mysteries of God that had previously been revealed to Jews like himself were now available to everyone. In Ephesians 4, Paul urges them – in light of the great opportunity for unity that the gospel affords – to live with unified maturity, following up in Ephesians 5 to remind them to reject any improprieties (sexual or otherwise) that could undermine that unity or maturity.

Note the lack of fear mongering! Paul isn’t trying to get them riled up and afraid, he just wants them to live a blessed life. For the rest of that fifth chapter, and going into the sixth, Paul begins to break down how that life of unified maturity applies to various common relationships – between spouses, from children to parents, even from masters to slaves (which in current vernacular is more like boss to servant).

This is the point where Paul then writes this iconic passage:

“Finally, be strong in the Lord, and in his mighty power. Put on the full armor of God, so that you can take your stand against the devil’s schemes” (Eph. 6:10 NIV).

Once you read it in context, it becomes clear – the image isn’t an armed vigilante gearing up, but of a peace officer who vows to serve and protect.

Paul wants the Ephesians to have the armor of God, not in order to strike back at their enemies but to preserve the unity and maturity they are supposed to live out as a witness to others. This is why Paul has to remind them in verse 12 that their enemies aren’t flesh-and-blood people because he knows that it’s easy for people from differing cultural and ethnic backgrounds to fight and feud with each other. This is why he refers to having feet covered with a readiness to share a gospel of peace. Paul isn’t trying to inject fear, he’s trying to remove it.

Don’t Use Fear as a Motivator

But therein lies the rub – often, the people most often who are governed by fear are those who are supposed to be trained to rise above it – actual peace officers. And when officers are, to use the language that is most often employed in defense of these kinds of shootings, “afraid for their lives” then the kind of snap judgments that result in these shootings are often driven by fear.

And fear can be a useful emotion. It can help motivate us to act, in order to neutralize a potentially deadly threat. Soldiers are often trained through the use of fear. A broadened sense of fear can promote the tribal instinct to band together against a dangerous Other.

Unfortunately, too many churches are doing exactly that – promoting a misunderstanding of Ephesians 6 by teaching people they should be afraid of people who aren’t like them, and that they should strike back against those trying to take away their religious freedoms. This climate of fear is toxic for our faith, which is part of the reason why so many churches are in decline. Evangelicals – particularly white evangelical leaders – tend to use fear as a motivator, and not only does it endanger black lives, but it betrays the very Scripture that they profess to love.

But 1 John 4:18 tells us that perfect love casts out fear. So this is where God’s people need to live. Where there is fear – especially when that fear is fed by anti-black bias – it needs to be honestly and consistently addressed and rectified. And those of us who carry firearms, whether as part of law enforcement or for other reasons, absolutely MUST be willing to confront those fears and admit those biases if we want these kinds of tragic shootings to stop.

More importantly, we cannot afford to wait for police agencies to do this work on their own. If we are to hold police accountable to the motto of “serve and protect,” we must also be willing to model servant leadership, extending both grace and discipline in equal measure. Churches full of Christ-following, Spirit-led people can create a spiritual climate where all of God’s people can be loved and valued, and in places where that is happening, it’s easier to hold accountable those who twist Scripture out of context to justify their violence, particularly when that violence is racialized.

If police forces are supposed to serve and protect, let’s be people who love to serve, creating an environment that’s worth protecting. In 2021, the church doesn’t need more soldiers of fear, it needs more servants of peace.

by Alex Leeds Matthews | Sep 18, 2018 | Headline News, Social Justice |

Asale Chandler holds a picture of her son, Yalani Chinyamurindi, who was murdered at age 19. Now, Chandler is a running for the Board of Supervisors in San Francisco. (Alex Leeds Matthews/California Healthline)

SACRAMENTO, Calif. — More than three years have passed since Asale Chandler’s teenage son was murdered in San Francisco. But Chandler said it feels as though it has been only three days.

The anguish doesn’t get better, said Chandler, a 55-year-old community activist from San Francisco at a recent rally. “It gets worse.”

Chandler’s 19-year-old son, Yalani Chinyamurindi, was one of four young black men who were shot and killed in January 2015 while sitting in a Honda Civic in the city’s Hayes Valley neighborhood. One man has been arrested in connection with the shooting.

Chandler prayed, protested and communed with other mothers — and brothers, sisters, aunts and uncles — who have lost their loved ones to violence.

The “Mothers Fight Back!” rally came amid ongoing unrest over the police shootings of unarmed black men, including Stephon Clark, who was killed in his grandmother’s backyard in Sacramento in March. His death sparked large-scale protests that blocked traffic and disrupted Sacramento Kings basketball games.

But attendees of the rally noted they were speaking out against violence of all kinds, not just police brutality. They said they took to the Capitol steps to grab the attention of lawmakers and journalists.

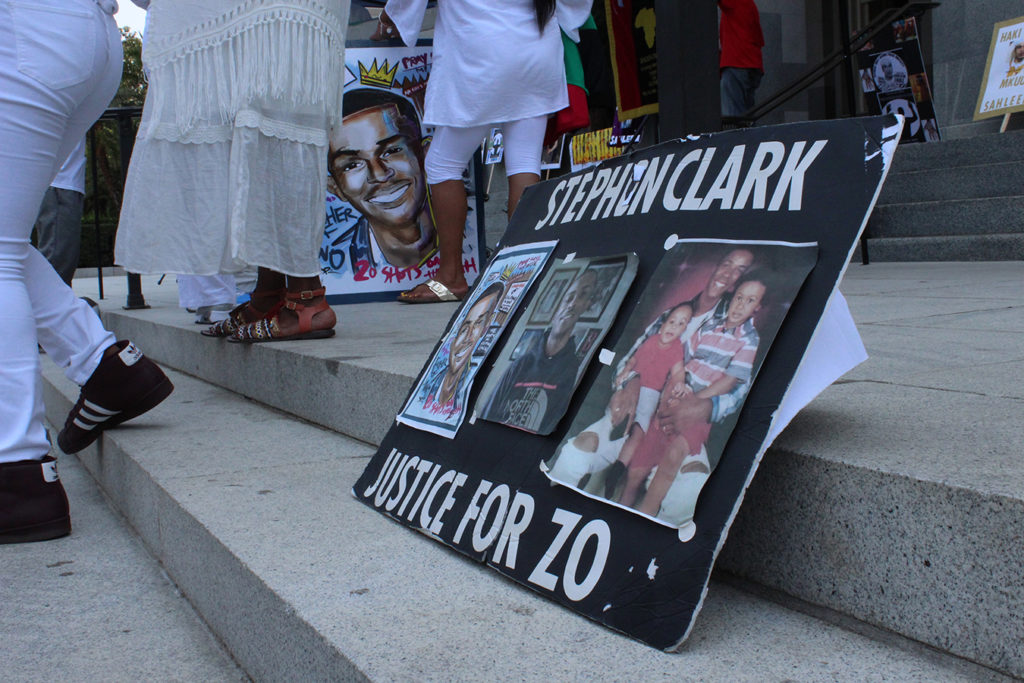

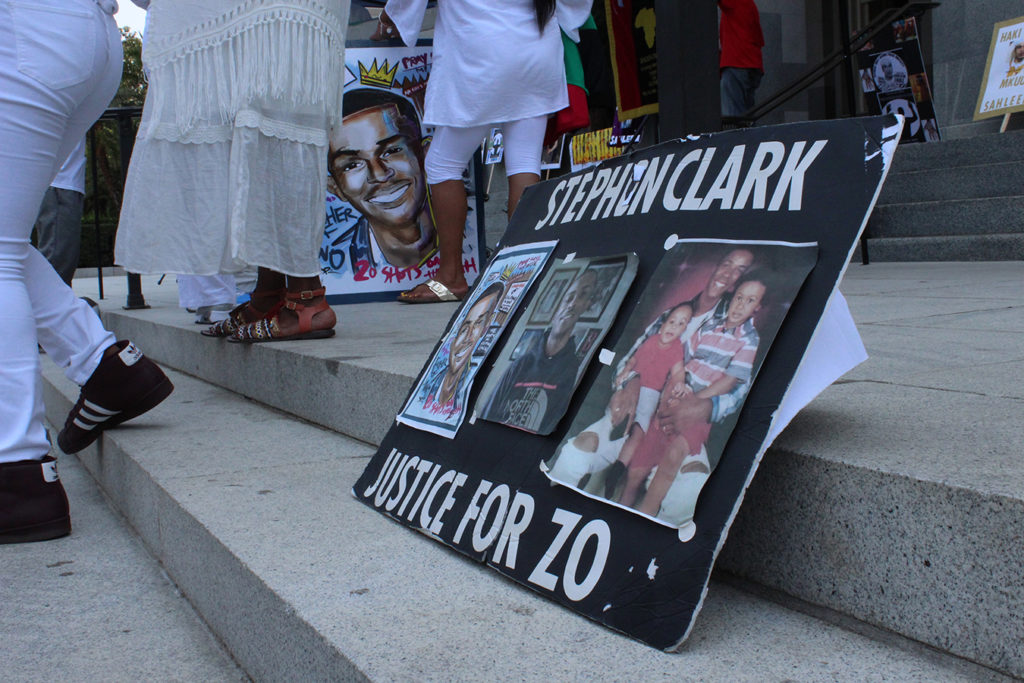

A poster commemorating Stephon Clark, who was killed by Sacramento Police in March, sits on the Capitol’s steps during the Mothers Fight Back! rally. (Alex Leeds Matthews/California Healthline)

A few, like Chandler, are running for public office. Others participated to support their loved ones and join in solidarity with other mothers.

“You do want to connect to a mother or a father who’s been through it,” Chandler said. She hasn’t found solace through therapy or medication, but said being around other mothers whose lives were also transformed by violence is “the true medicine.”

The rally was passionate, but it wasn’t as pugnacious as its name might suggest. The moms came bearing snacks, handcrafted posters and children’s books. They sang and said prayers.

Participants said they are facing a dire mental health crisis fueled by violence, trauma and uncertainty.

“It’s traumatic for all of us. … We’re scared to death. We don’t know what to do, we don’t know how to act,” said Leia Schenk, 40, a social services worker in Sacramento, who is close with Sahleem Tindle’s family. Tindle was shot and killed by BART police near the West Oakland BART station in January.

Asale Chandler’s son was murdered more than three years ago in San Francisco. At a recent rally, the community activist participated in a Hebrew “mother’s prayer” at the Mothers Fight Back! rally at the Capitol. (Alex Leeds Matthews/California Healthline)

Schenk said she struggles with the emotional fallout from the violence and fears for her children, particularly her two black sons. “It’s a helluva way to live,” she said.

Black children die from gun-related homicides at a rate nearly 10 times higher than that of white children, according to a 2017 study in the American Academy of Pediatrics. Another study published a few weeks ago showed that black men are at risk of being killed by police at a rate about triple that of white men.

The statistical differences are important, said Chet Hewitt, president and CEO of the Sierra Health Foundation, which awards grants to reduce health disparities.

However, the numbers don’t reveal the mental and physical pain that afflicts victims and their communities contending with violence, said Hewitt, who did not attend the rally.

“You are constantly on high alert, and you are constantly in a state of mourning,” said Cat Brooks, an Oakland mayoral candidate and a co-founder of the Anti Police-Terror Project.

Brooks, who has a 12-year-old daughter, attended the gathering to address the struggle many black parents encounter trying to protect their children from violence.

“Because there is no rhyme or reason to our people getting killed, that means there’s no one to tactically figure out how to avoid it,” said Brooks, 41. “We teach our children everything we can about how to stay alive.”

A poster commemorating Stephon Clark, who was killed by Sacramento police in March, sits on the Capitol’s steps during the Mothers Fight Back! rally.

That trauma, fear and uncertainty has measurable effects on health.

According to the American Psychological Association, more than 25 percent of African-American youths exposed to violence are considered at risk for post-traumatic stress disorder. Symptoms of PTSD include anxiety, flashbacks and difficulty sleeping.

Community cohesion can help people heal from acts of violence, but violence can also erode that sense of togetherness, said Flo Cofer, director of state policy for Public Health Advocates, a nonprofit organization that works to address health disparities.

Many of the communities most affected by violence also face other physical and social challenges like poverty, hunger and educational obstacles, she said.

“That’s part of the reason why the violence is so devastating. This is happening in a place where trauma is the air they breathe,” Cofer said in a phone interview.

At the rally, the low-key gathering of approximately 50 people consisted mainly of women and children. Moms parked strollers under a tent while their former occupants munched on crackers or toddled on the Capitol steps.

As one little girl, dressed in flowery overalls and shimmery sandals, danced to the “Circle of Life” song, adults and older children, dressed in white, surrounded her, clapping to the beat.

When the mothers gathered for a Hebrew “mother’s prayer,” Chandler stood near the front with her arms stretched above her head.

She is running for the Board of Supervisors in San Francisco to address the violence in her Bayview-Hunters Point neighborhood. “I’ve seen nothing but yellow tape, and it messed me up so badly,” she said.

Yolanda Banks Reed led the prayer.

Banks Reed’s son was the young man who was killed nearly seven months ago near the BART station. She said she knows the mental toll will be lifelong.

“It’s a life sentence for a mother,” she said. “A mother should not lose her children.”

Article published courtesy of California Healthline

by Urban Faith Staff | Jun 18, 2012 | Feature, Headline News |

ROAD TO REDEMPTION: Rodney King, 47, was found dead in his swimming pool on Sunday, June 17. In April, he was a featured author at the LA Times Festival of Books, where he discussed his autobiography, 'The Riot Within.' (Photo: Susan J. Rose/Newscom)

Rodney King’s untimely death over the weekend has led to a lot of conversations about his significance as a key civil rights figure. King, of course, gained fame for the 1991 videotaped beating by Los Angeles cops that he endured and the subsequent race riot that followed in 1992 after the officers were acquitted of any wrongdoing. He then became an unlikely voice of reason when, in the midst of the deadly and destructive rioting, he famously asked, “Can we all just get along?” Sadly, that question still echoes today after each new racially charged issue or controversy that erupts in the media.

But what will be King’s lasting legacy? By his own admission, he was not a perfect man. In fact, drunk driving and alleged substance abuse were the reasons he was pulled over by the L.A. cops initially in 1991, and he continued to struggle with drugs and alcohol apparently until the night of his death. In a Los Angeles Times post, reporter Ken Streeter recalls his series of interviews with King this year and confirms that King was still drinking and still smoking pot (he said for medical reasons).

So, King doesn’t exactly fit the classic image of the heroic civil rights icon. Yet, he stands as an important symbol in our nation’s uneasy saga of racial unrest and our stutter steps toward reconciliation.

Writing at The Root, Sylvester Monroe speaks of King as a “symbol” whose pain and missteps were not in vain. Last year at Poynter.org, Steve Myers observed how citizen journalism has changed since that infamous video of King being beaten by police. An Associated Press report at HuffPost’s Black Voices attempts to summarize King’s significance in shining a light on the injustices of racial profiling and police brutality in urban law enforcement. The article features an interview with Lou Cannon, author of Official Negligence: How Rodney King and the Riots Changed Los Angeles and the LAPD.

“The King beating and trial set in motion overdue reforms in the LAPD and that had a ripple effect on law enforcement throughout the country,” Cannon explains. Indeed, under L.A. police Chief William Bratton in the 2000s, the department began focusing on community policing, hired more minority officers, and worked to heal tensions between the police and minority communities who continued to protest racial profiling and excessive use of force.

In the post-Rodney King world, adds Cannon, “It became more perilous to pull someone over for driving while black.”

To his credit, King was well aware of his shortcomings and shared his story in an autobiography released earlier this year to mark the 20th anniversary of the L.A. riots. In The Riot Within: My Journey from Rebellion to Redemption, King came clean about his failures and his continued struggles with alcohol addiction, but also about how God had helped him begin to turn his life around.

In a poignant interview with the Canadian public radio program Q with Jian Ghomeshi, King talked about his book and expressed optimism about both his own future and the state of race relations in the United States.

What do you view as Rodney King’s legacy? What does his complicated journey say about race relations in America? Will he rightly be remembered a civil rights icon?