by Christine A. Scheller | Nov 25, 2018 | Headline News |

“Bittersweet” is how Joshua Canada describes his memories of working to improve the experience of students of color at Taylor University in Upland, Indiana, when he was a student there.

“Bittersweet” is how Joshua Canada describes his memories of working to improve the experience of students of color at Taylor University in Upland, Indiana, when he was a student there.

As vice president of the Multiethnic Student Association at Taylor, Canada successfully petitioned the school to restructure its ethnic recruiter position and to re-establish its director of multiethnic student services position. He was also an original member of Taylor Black Men, a student group that provided support for young men who didn’t necessarily feel comfortable discussing the unique challenges they faced with White classmates.

“I was really excited that I was able to do that, but there’s also this sadness that I have now because, although I felt like it was important, it painted a lot of my senior year,” said Canada, who occasionally writes for UrbanFaith.

He was compelled to act, he said, because he feared that no one else would if he didn’t. “I was blessed enough that I had a lot of coping skills,” he explained. “I could ‘code switch,’ and sometimes get in that middle world, where I could deal with both cultures, but there were several students who couldn’t.”

It is those students that concern a number of professionals who work at Christian colleges around the nation, and especially those affiliated with the Council of Christian Colleges and Universities. The CCCU, an international association of Christian institutions of higher education, seeks to provide resources and support for the students, faculty, and administrations of its member schools. Assisting students of color with their often difficult transition into the culture of predominately White Christian campuses has become one of its chief missions during its 36 years of existence.

Slow but Steady Progress

Twelve years ago the CCCU established a Racial Harmony Award to celebrate the achievements of its member institutions in the areas of “diversity, racial harmony, and reconciliation.”

In 2001, the organization’s board affirmed its commitment. “If we do not bring the issues of racial-ethnic reconciliation and multi-ethnicity into the mainstream of Christian higher education, our campuses will always stay on the outside fringes,” remarked Sam Barkat, former board member and provost of Nyack College in Nyack, New York.

CCCU schools have made “steady gains” since then, according to a report co-authored by Robert Reyes, research director at Goshen College’s Center for Intercultural Teaching and Learning and a member of CCCU’s Commission for Advancing Intercultural Competencies.

Robert Reyes: “We’re supposed to be unified as Christians.”

Reyes and his colleagues found that overall percentage of students of color increased from 16.6 percent to 19.9 percent at CCCU schools between 2003 and 2009 and graduation rates for these students also increased, from 14.8 percent to 17 percent, which still only adds up to a tiny fraction of all students at CCCU’s 115 North American affiliate schools.

According to Reyes, CCCU has a new research director and is developing a proactive research agenda related to these issues. This kind of research “creates a certain level of anxiety,” he said, because it categorizes people and theoretically separates us when we’re supposed to be unified as Christians. “I think it’s a misunderstanding of what the unity of the body is, and what unity means in the Christian faith,” said Reyes.

For those, like Reyes and Canada, who are engaged in diversity work on CCCU campuses, the task can feel like slogging through a murky swamp. UrbanFaith talked to current and former diversity workers at nine CCCU schools about their efforts and experiences. We repeatedly heard that students of color face unique challenges on these campuses and that CCCU schools are not always prepared, or willing, to deal with them. We also heard about successes and how challenging they can be.

The Problem — a Whole Different God

Multiple sources said students of color at Christian colleges are routinely harassed with racially insensitive jokes and comments by members of their campus communities, for example, and that this harassment is sometimes not taken seriously enough by school administrators.

When racism isn’t overt, students often feel like they won’t be accepted by their school communities unless they suppress their ethnic identities. Many students feel profoundly lonely on majority-White CCCU campuses, our sources said.

Dante Upshaw, for example, has been both a student and a staff member at evangelical schools. He recalled the challenge that worship presented when he was a student at Moody Bible Institute in Chicago.

“For the average White student, it’s an easy crossover. … It’s kind of this big youth group. But for the Black student, the Hispanic student, this is a whole different God,” said Upshaw.

He was unfamiliar with the songs that were sung in chapel, for example, and found himself in conversations about what constitutes godly worship. “I was a young person having to articulate and defend. That’s a lot of pressure for a freshman,” said Upshaw.

Monica Smith: “We haven’t gone far enough.”

Monica Smith has seen the same phenomenon played out on her school’s campus. As assistant to the provost for multicultural concerns at Eastern University in St. Davids, Pennsylvania, she said students of color once complained to her about being judged for skipping chapel services that felt culturally foreign to them. They were told they should be able to worship no matter what kind of music or speaker was up front. “The retort was, ‘You’re right, so why can’t it sound like what I’m used to?’” said Smith, who also teaches courses in social work.

Smith and her colleagues have identified four specific areas of challenge that confront students of color at Eastern: financial, academic, social, and spiritual. “If students are struggling in those areas, they really can’t pay attention in the classroom,” said Smith.

The university is making headway, but it’s slow, she said. “As much as we have done administratively and in the academic arena, I still don’t know that our university’s administration has gone far enough with this.”

Institutional Challenges — Like Turning the Titanic

Upshaw served as a minority recruiting officer and assistant director of the office of multi-cultural development at Wheaton College in Wheaton, Illinois, in the early 2000s. He said the number of non-White students who were in pain over their experience at the school would have been as big as his admissions file.

He recalled leaving school one day to commute home to Chicago when he saw a student of color sitting on the stairs “like a lonely puppy.” Upshaw read the student’s demeanor as saying, “You about to leave me here, man? You’re actually going to leave and go to your home?”

Dante Upshaw: “Too many students felt alone.”

“There were just too many students like that, where they felt so alone on this beautiful, immaculate campus with great food service and great athletics,” Upshaw said. “Those were some hard years.”

In response to the need he saw, Upshaw founded Global Urban Perspectives, a multiethnic student group devoted to urban issues. He believes it was successful in part because it helped foster healthy relationships.

“The fact that we were together in a safe setting where we were given space to be ourselves, I think that really struck a chord with many of the students,” he said.

“It’s a wealthy system, it’s an established system, it’s a strong historic system, and it’s a very Christian religious system,” said Upshaw of the institutional challenges he faced at Wheaton. “Changing a system like that would be akin to turning the Titanic … It is going to take a long time, and it’s going to be real slow.”

Even so, Upshaw said he saw “the ship” turn quickly when influential individuals decided to act. Too often, though, he saw inaction born of the fear of alienating potential donors. Upshaw left the school, in part, because he was frustrated with the administration’s commitment to a broadly applied quota system that he felt undermined his efforts to recruit more students of color.

Additive and Subtractive Approaches

Although Joshua Canada is ambivalent about his experience at Taylor University, he returned there for graduate school and now serves as an adviser to the Black Student Union at Westmont College in Santa Barbara, California, where he is also a residence director. He said not all students of color struggle with the racial dynamics on their campuses and some students rarely do.

“In their ethnic development, they’re not dealing with this tension, or this is what they’ve done their whole life and they know how to do this,” said Canada.

Joshua Canada: “To be successful, our vision of being multicultural must be transformative.”

He described two approaches to multiculturalism, one that is additive and one that is subtractive. With the additive approach, elements of non-European culture are added to the core culture, he said, and with the subtractive approach, people of color drop elements of their culture to assimilate into the majority culture.

“Students feel it, if it’s additive,” Canada said. “We did Black History Month. We did Martin Luther King Jr. Day. It’s a nice gesture, but people realize it isn’t who we are.”

“To really be successful, we have to come to a place where our vision of being multicultural is more transformative and then it really does change aspects of the institution. It really does change the big-picture experience, and not in a way that is unfaithful to the history of the institution, but that maybe acknowledges gaps.”

George Yancey is a University of North Texas sociologist and the author of numerous books, including Neither Jew nor Greek: Exploring Issues of Racial Diversity on Protestant College Campuses. (Canada’s UrbanFaith interview with Yancey prompted us to investigate the issue further.) According to Yancey, the task of student retention at Christian colleges is complicated by the evangelical community’s habitual conflation of faith and culture.

“There’s an issue in retaining students of color in higher education in general,” he told UrbanFaith, “but I think Christian College campuses have even more of a challenge because of some of the dynamics that are there. A lot of times, the way the faith is practiced is racialized. People don’t always realize it.”

Nurturing Dialogue

It wasn’t only African Americans, however, who recounted stories about the challenges students of color face at CCCU institutions. Jon Purple is dean for student life programs at Cedarville University in Cedarville, Ohio. He recalls the mother of an incoming student crying when she dropped her young Black son off at the rural Ohio campus, and not just because he was leaving home.

“She was in tears and was afraid to leave her son here, because of very real fears that some good-ol’ White boys might accost her son,” said Purple.

Continued on Page 2.

by Associated Press | Oct 25, 2018 | Headline News |

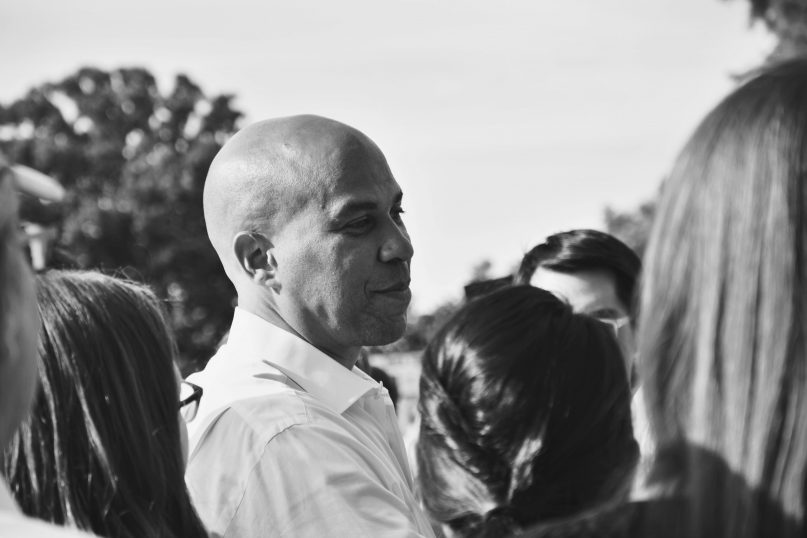

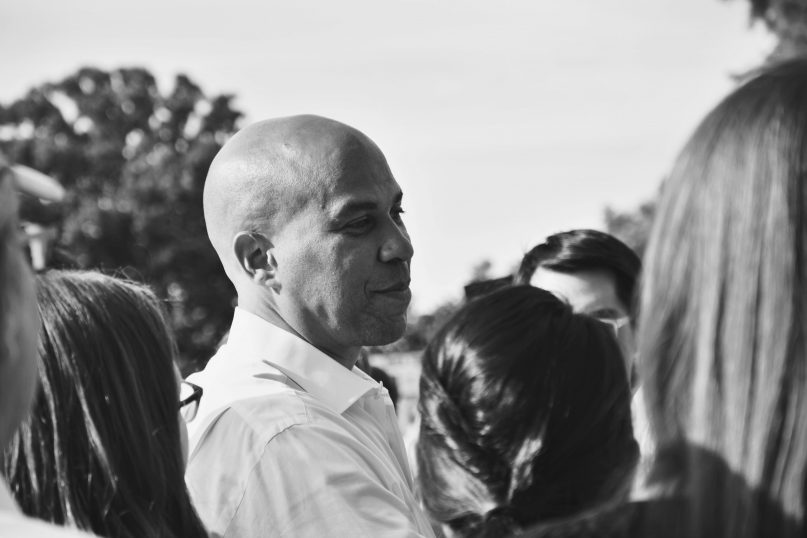

Cory Booker meets with demonstrators at a protest in Washington, D.C., on June 28, 2017. RNS photo by Jack Jenkins

Questions about religion can paralyze some politicians, but not Cory Booker.

If anything, the topic seems to relax him. Sitting in his spacious but spartan office on Capitol Hill in early October, the senator propped his sneakered feet up on his desk and waxed poetic about spiritual matters, bouncing between discussions of Jesus’ disciples, housing policy and his own religious practices.

“When I get up in the morning, I meditate,” the New Jersey Democrat said, a practice he has often linked to his spiritual health. He paused for a moment, then quickly corrected himself: “Actually, I pray on my knees, and then I meditate.”

Booker’s comfort with his faith is unusual for Democrats in Washington, but it’s standard fare for the 49-year-old former mayor of Newark and has even become a mainstay of his blossoming political persona: Even the hyperbole-averse Associated Press recently compared him to an “evangelical minister” after Booker addressed a group of Democrats in Iowa.

AP had good cause: The decidedly progressive speech, which many speculated was a warmup for a 2020 presidential run, was peppered with talk about “faithfulness” and “grace.” Booker closed by citing Amos 5:24 (“But let justice roll on like a river, righteousness like a never-failing stream!”) before shouting “Amen!” over the roaring crowd.

Asked about his tendency to fuse the political with the spiritual, Booker shrugged.

“I don’t know how many speeches of mine you can listen to and not have me bring up faith,” he said. He noted he had just come from a Senate Judiciary Committee meeting where he had lifted a line from his stump speech: “Before you tell me about your religion, first show it to me in how you treat other people.”

The sentiment, along with a message of unity that he brands as a “new civic gospel,” is generating buzz among Democrats. But Booker’s brand of public religiosity is especially attractive to an oft-forgotten but increasingly powerful group: the amorphous subset of religious Americans sometimes known as the religious left.

If he does run for president, as many expect, Booker may be one of the first Democratic candidates in decades to actively cultivate support from religious progressives.

A favorite of lefty faithful

Raised in an African Methodist Episcopal church and now a member of a National Baptist church in Newark, Booker has become a fixture at left-leaning religious gatherings as far back as 2014, when he showed up at a summit hosted by Sojourners, a Christian social justice organization. He “basically preached a sermon at the opening reception,” tweeted one organizer of the event.

In 2017, Booker attended a protest outside the U.S. Capitol hosted by the Rev. William Barber II, a prominent religious progressive who was there to denounce the Republican-led effort to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act. Earlier this year, Booker spoke at the Festival of Homiletics, a preaching conference attended by primarily white, liberal mainline clergy.

His appearance at these events has often resulted in standing ovations, and near endorsements.

“I don’t hope to move to New Jersey, but I do hope to vote for you someday, if you catch my drift,” the Rev. David Howell, the Presbyterian founder of the Festival of Homiletics, said while introducing Booker in May.

Booker claims that his faith is not partisan: He said religion is a way to reach across the aisle, and Republican Sen. John Thune is reportedly a member of his Bible study (along with New York Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand, another potential Democratic presidential hopeful). But if Booker is unapologetic about his faith, he’s also unapologetic about the potential political effect of his God-talk.

“I think Democrats make the mistake often of ceding that territory to Republicans of faith,” Booker said.

Sen. Cory Booker, D-N.J., in his Washington office on Oct. 17, 2018. RNS photo by Jack Jenkins

Eric Gregory, who studied with Booker at Oxford University as a Rhodes scholar and at Yale, said the senator’s fascination with faith is nothing new.

“He certainly has always been religiously musical,” said Gregory, now a professor of religion and chair of the humanities council at Princeton University.

Booker’s fluency with faith isn’t restricted to Christianity. His Facebook feed includes mentions of the Buddha, he referenced the Hindu god Shiva in a recent interview, and at Oxford in the 1990s he chaired the L’Chaim Society.

“He was always curious about diving deeply into different religious traditions and trying to understand them but also find wisdom within them,” said Gregory.

Still, Booker roots his personal faith in Christianity, particularly the black church tradition in which he was reared.

“I will talk about my faith, and I also talk about other faiths I study,” Booker told Religion News Service, sitting beneath an image of Mahatma Gandhi, one of the few adornments on his office walls. “I’ve studied Torah for years. Hinduism I’ve studied a lot. Islam, I’ve studied some, and I’ve been enriched by my study. But, for me, the values of my life are guided by my belief in the Bible and in Jesus.”

It’s an approach to religion — multifaith, LGBTQ-inclusive, liberation theology-influenced and social-justice focused — that jibes perfectly with the makeup of the liberal coalition.

“The life of Jesus is very impactful to me and very important to me,” he said. “He lived a life committed to dealing with issues of the poor and the sick. The folks that other folks disregard, disrespect or often oppress. He lived this life of radical love that is a standard that I fail to reach every single day, but that really motivates me in what I do.”

But Booker insisted his connection with religious left leaders such as Barber, who spoke at the 2016 Democratic National Convention, has less to do with political angling and more to do with a natural overlap of shared values.

“I find kinship with people I find inspiration from — people I would love to be more like,” he said. “Rev. Barber is powerful. To me, his charisma speaks, in an instructive way, towards my heart and my being. He is somebody who believes that being poor is not a sin or that poverty is a sin.”

Riding progressive religious power

Progressive religion, drowned out in recent decades by the well-organized religious right, has been revived by the rise of President Trump. Within weeks of the 2016 election, left-leaning religious groups saw spikes in funding. Their coalitions became a crucial part of the “resistance” to Trump’s travel ban, the repeal of the ACA and the separation of families along the U.S.-Mexico border. Leaders such as Barber and Linda Sarsour, a prominent Muslim activist and core organizer of the Women’s March, have been elevated to the national stage.

As their influence increased, so too did side-by-side appearances with potential 2020 presidential hopefuls such as Booker, Sen. Elizabeth Warren, D-Mass.; Sen. Kamala Harris, D-Calif.; and others.

For modern religious progressives the new attention comes with a dilemma: What does it mean not only to protest power but to influence it — or even be courted by it?

“I think faith communities, particularly the religious left, need to become even more aware of the significant, for lack of a better word, lobbying power that they have,” said the Rev. Kelly Brown Douglas, a theology professor and dean of Episcopal Divinity School at Union Theological Seminary in New York.

Marie Griffith, director of the John C. Danforth Center on Religion and Politics at Washington University in St. Louis, said the shift harks back to the era of President Carter, who ran as a Southern Baptist Democrat.

“I would absolutely see (Carter) as exemplifying this progressive Christian vision,” she said, noting that after he lost re-election the progressive religious spirit that elected him “went underground.” In a sense, the rise of Bookers and Barbers signals a return to form.

“They’ve got their boldness back, and they’re willing to speak in the name of religion and not hide their light under a bushel,” she said.

Douglas also highlighted the importance of Booker’s attachment to the black church.

“Historically, black communities have relied on the leadership and the wisdom of their faith leaders,” she said.

It’s unclear whether white Democrats of faith, whose numbers continue to dwindle, can be successfully courted along faith lines, despite numerous attempts over the years by groups such as Sojourners and others. But appealing to the faith of nonwhite Democrats, according to data unveiled earlier this year by Pew Research, suggests that may be a crucial long-term strategy for those seeking to turn red states blue. Although states with higher religious attendance and expression tend to be Republican, nonwhite populations in those states skew highly religious and deeply Democratic.

Douglas pointed out that Booker already exhibited the power of the black faith community in the 2017 Alabama senate race. As Republican Roy Moore battled accusations of child sex abuse, Democrat Doug Jones reached out to black voters, using the last days before the election to campaign at several black churches.

Standing next to Jones during those church visits was Booker.

Two days later, analysts largely credited Jones’ victory to massive black voter turnout.

Preaching a new ‘civic gospel’

Booker is not the only potential presidential hopeful vying for the religious left’s attention. Warren, Harris and others are also winning hearts among the faithful. Booker has also faced hard questions from the left, including religious progressives, for taking large donations from Wall Street.

He’d likely also have to address the concerns of slightly less than a third of Democrats who do not claim a religious affiliation, many of whom are uneasy with politicians who cite faith as a guide.

Sen. Cory Booker, D-N.J., addresses Festival of Homiletics attendees at Metropolitan AME Church on May 22, 2018, in Washington. RNS photo by Jack Jenkins

But Booker is already working out ways to talk to them, too.

“I prefer to hang out with nice, kind atheists than mean Christians any day,” he has often said.

Meanwhile, the larger struggle may be to convert the religious left into an organized political force.

Gregory identifies “a kind of paralyzing despair or prophetic critique that disables the possibility of politics more than enabling it. In some ways, I think one of the reasons why Senator Booker often gets a lot of enthusiastic reception is because he is capable of recognizing severe challenges but also not giving in to the despair or withdrawal.”

Booker’s optimism is embodied in his concept of a “civic gospel,” a vision for a politics devoid of the “meanness” and “moral vandalism” that he sees in current political discourse, especially from Trump.

“I think God is love,” Booker said, leaning across his desk. “I think God is justice. I think that the ideals of this country are in line with my faith. I don’t need to talk about religion to talk about those ideals that all Americans hold dear.”

Perhaps Booker is something of an evangelical — or at least an evangelist — for this ecumenical sense that politics and religion are not mutually exclusive, all while reaching those outside the religious fold with a broader inclusive message. Whether the faithful, literal and figurative, will rally around that idea will likely be the question of his next two years.

“Every speech I give, I will not yield from talking about that revival of civic grace,” he said.

by Shari Noland | Sep 13, 2018 | Commentary |

For some people speaking up when they know they’re right, or when they see an injustice, is just part of who they are. They feel compelled to take action. Not me. I spent a big part of my younger years screaming inside about things that frustrated me at work, church, and even in my personal life, but the outrage never escaped the audience in my head. In real-time, I was just sitting there…silent…paralyzed with fear over whether I would be hurt professionally or personally if I faced the conflict head-on and said something out loud. I was well into my thirties before I realized how liberating it can be to use your voice while fighting for a cause bigger than yourself.

That’s why Kathy Khang’s latest book, Raise Your Voice: Why We Stay Silent and How to Speak Up, resonates with me. Khang offers practical advice and forward-thinking leadership from a Christian perspective on how to find your own personal voice for the good of the community and sharing God’s Word — particularly when race, ethnicity, and gender are at play. But even for her, it took time to get to the place where she is now.

“As a Korean American woman, I really wrestled with whether or not it was appropriate to raise my voice, whether I had anything worth saying,” Khang says. “Maybe if I had something worth saying, would anyone listen? Would anyone care?”

Khang, a columnist for Sojourners magazine and a writer for Duke University’s Faith & Leadership, the online magazine of leadership education at Duke Divinity, talked with Urban Faith about her new book, the politics of race and evangelism, being a woman of color with something to say, and why many people don’t speak up.

You mentioned that finding your voice has been part of a 10-year process. Can you tell me more about what you were struggling with and how your faith helped you push through it to complete the book?

This wasn’t, you know, a 10-year process in my twenties. This is my late thirties, early forties, where I’ve already been a professional journalist. There aren’t a ton of examples of Korean-American, Asian-American women, women of color in safe circles writing books. There are more now, but definitely not when I was in my formative years. And those were not the authors I read to shape my faith, to shape my Christian worldview. Those books were all written by white men, by and large, and a lot of white women. And so, I just had to really work through why is it that I feel like I have nothing worth saying when clearly there are tons of people who have no problem figuring out that they have something to say. Having to walk through that with myself and with God. Spending time listening to God with the help of a spiritual director and some great Christian mentors, and supervisors who were encouraging me and saying, “You know, you do have something to say.”

If you could go back in time and talk to the 24-year-old you, what would you tell her about race?

I would say to her, “Keep doing what you are doing and learning vocationally.” So in my twenties, I was a newspaper reporter and I’d say ‘Don’t be afraid of talking with your editors and fighting for the story or fighting for the wording because it matters.’ I think there were a lot of times where I thought, ‘Well, this isn’t the fight I wanna fight.’ And there’s wisdom to that. But I think that there were other times where I was just so worried I would get fired. I would also tell that 20-something self that it’s important to care for yourself in order to care for your community. I learned that later — the idea of being a self-sacrificing Godly woman is communicated in various ways in different cultures and in different churches. I certainly felt it. I wish I had heard that more consistently in my twenties to encourage me, you know?

What is it that is holding people back from speaking up and being who God called them to be?

Fear. And some of that fear is rooted in a fear of a failure. For me, I’m a bit of a recovering perfectionist. I would encourage people to not only think about the cost of speaking up and raising your voice, but also the cost of continually remaining silent. What does that do? What does that say about what you say you believe in? What does that do to your soul and who God is encouraging you to become?

You’ve been outspoken about racism in the church, especially on social media. How we can come together when we see the world so differently?

You raise your voice mindful of the backlash. I don’t wanna be overly dramatic, but I also don’t want to ignore the fact that I know many, many people of color, myself included, and particularly women of color, who speak out against racism in the church and we get the most horrifying and disgusting responses. You get an email. You get a direct message. You get a tweet back at you. I will be very honest, I’m not sure on this side of heaven we will see a time where that gap is fully bridged. However, I think it is very important that the work is not left up to people of color to raise their voices. We need teachers, preachers, authors, artists to continue to speak into those spaces, to call that out and to present the various alternatives. What would this world look like? What would the church look like if we were able to bridge that divide? What will the world and the church look like if we do not? Because it can’t be left to people of color. We need our white allies and we need them not to be afraid of making mistakes and offending and screwing up.

by C.B. Fletcher, Urban Faith Contributing Writer | Mar 29, 2017 | Social Justice |

Imagine a time when members of the Black community looked out for one another. Neighbors were more like family, children were safe, and troubling news such as 26 open missing persons cases were incredibly rare.

There is an unrelenting rage boiling in our community due to the lack of coverage or collaborative effort to find the missing Black and Latina girls in Washington D.C. However, we can point fingers, or even yell at the police, city officials and federal government, but what are we doing to protect our own children?

While there has been coverage from major news outlets and support from organizations such as BET and The Women’s March on Washington Organization, some would argue that the issue is larger than one may think.

There have been many cases of missing children who are White that have received major state and national coverage, along with extensive, coordinated searches, but when 14 Black girls go missing, it is a different story.

The issue is not that there is no coverage. It is that this issue became important when it became a hashtag. It should have never gotten this far.

What can we really ask of our civil servants?

There are mixed messages on the severity of this situation. Some outlets say there are 14 girls missing, while others are implying that the girls aren’t really in danger and are labeling them “runaways.”

While that assumption is not stressed by D.C. Mayor Muriel E. Bowser or other public officials, there is still a permeating, public message that lessens the concern of onlookers across the nation.

Since gaining national attention, the news of our missing girls has produced town halls filled with tears and frustration. However we are still left to wonder, “What else can be done?”

New York resident Aura Severino is one of many Americans following this story.

“Law enforcement needs to understand why they are [being] taken,” Aura says. “Are they victims of opportunity or targeted? These are questions that need to be asked to figure out what is being done with these girls. Once that is understood, moves can be made to prevent more girls from being taken and rescuing those who are already gone.”

Aura, a program manager in New York City, also feels that the family unit plays a huge role in making a difference. “Families need to educate their girls and boys about what is currently happening to encourage vigilant awareness,” she says.

Although local and state city officials are making strides to find the missing girls, one can’t help but notice that there is a lack of coverage on the fact that there are missing boys too. What is to be done when our boys, our future leaders who are raised to protect our communities and families, are also missing?

Atlanta resident Mario Jackson believes it all comes down to training and resources.

“There needs to be more neighborhood surveillance and trainings in kidnapping for D.C. Police,” Mario says. “I also believe in the old-school practice of neighborhood watches and communal security.”

Fortunately, it is being reported that Mayor Bowser is unrelenting in her efforts to address the number of missing person cases in D.C. However, some believe that addressing the issue starts right here in our own communities.

COMM’UNITY’

‘Unity’ plays a major role in “community,” and its members have a responsibility to be a part of it.

While Mayor Bowser attempts to reel in the community through her task force and other efforts, none of it matters without the support and action of the community. The task force will follow a procedure as deemed appropriate by the city, but how will the community light the beacon of hope?

Although New York-D.C. Native Aisha Jones commends the city’s efforts to make a difference, she charges us, the community, to do our part.

“We are so quick to save on the money and energy we put into our kids that we don’t worry about safety,” Aisha says. “Most of these girls are being abducted on the way home. Their parents are not picking them up from school or encouraging a buddy system or teaching them how to fight back.”

Like Mario, Aisha agrees that the proper resources are critical in resolving these issues.

“There should be self-defense classes for both boys and girls,” she says. “Also there is a responsibility to speak up if you see something. ‘Snitches get stitches’ does not apply when you see someone in danger.”

Take a look at BET’s compelling video on the recent news coverage below:

Weigh in below on how you and others can work to rebuild the community and protect our children.

by Adelle Banks | Jan 18, 2017 | Headline News |

(RNS) In one of his last official acts, President Obama has designated Sixteenth Street Baptist Church and other civil rights landmarks in Birmingham, Ala., as the Birmingham Civil Rights National Monument.

The designation protects the historic A.G. Gaston Motel in that city, where the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and other civil rights leaders had their 1963 campaign headquarters, as well as Kelly Ingram Park, where police turned hoses and dogs on civil rights protesters.

And it includes the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, where four girls died in 1963 after Ku Klux Klan members detonated more than a dozen sticks of dynamite outside the church basement.

“This national monument will fortify Birmingham’s place in American history and will speak volumes to the place of African-Americans in history,” said the Rev. Arthur Price Jr., pastor of the church, in a statement.

Obama’s proclamation also cites the role of Bethel Baptist Church, headquarters of the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights, and St. Paul United Methodist Church, from which protesters marched before being stopped by police dogs.

In his proclamation Thursday (Jan. 12), Obama said the various sites “all stand as a testament to the heroism of those who worked so hard to advance the cause of freedom.”

In other acts, all timed to Martin Luther King Jr. Day, which will be observed on Monday, the president designated the Freedom Riders National Monument in Anniston, Ala., and the Reconstruction Era National Monument in coastal South Carolina.

He cited the role of congregations in all three areas — from sheltering civil rights activists at Bethel Baptist Church to hosting mass meetings at First Baptist Church in Montgomery, Ala., to providing a school for former slaves at the Brick Baptist Church in St. Helena Island, S.C.

The designations instruct the National Park Service to manage the sites and consider them for visitor services and historic preservation.

“African-American history is American history and these monuments are testament to the people and places on the front-lines of our entire nation’s march toward a more perfect union,” said Interior Secretary Sally Jewell.

“Bittersweet” is how Joshua Canada describes his memories of working to improve the experience of students of color at Taylor University in Upland, Indiana, when he was a student there.

“Bittersweet” is how Joshua Canada describes his memories of working to improve the experience of students of color at Taylor University in Upland, Indiana, when he was a student there.