Students of color in special education are less likely to get the help they need – here are 3 ways teachers can do better

When I was a special education teacher at Myrtle Grove Elementary School in Miami in 2010, my colleagues and I recommended that a Black girl receive special education services because she had difficulty reading. However, her mother disagreed. When I asked her why, she explained that she, too, was identified as having a learning disability when she was a student.

She was put in a small classroom away from her other classmates. She remembered reading books below her grade level and frequent conflicts between her classmates and teachers. Because of this, she believed she received a lower-quality education. She didn’t want her daughter to go through the same experience.

Ultimately, the mother and I co-designed an individualized education plan – known in the world of special education as an IEP – for her daughter where she would be pulled out of class for only an hour a day for intensive reading instruction.

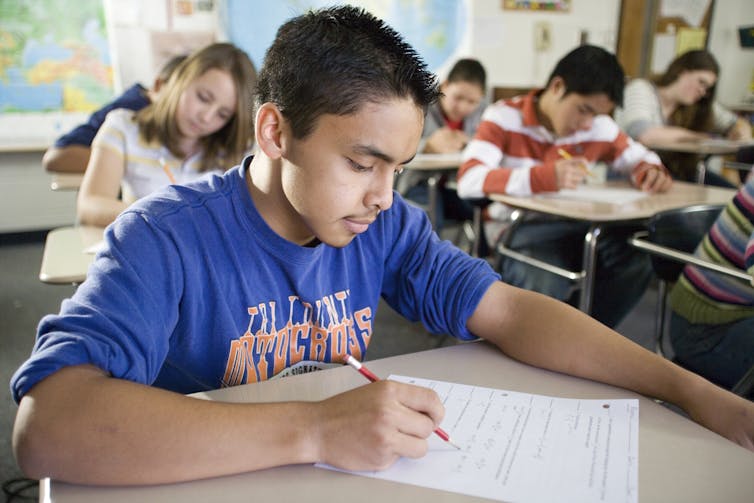

When compared to white students with disabilities, students of color with disabilities are more likely to be placed in separate classrooms. This may lead to lower educational outcomes for students of color in special education, as students with disabilities perform better in math and reading when in general education classrooms.

Researchers, such as University of Arizona education scholar Adai Tefera and CUNY-Hunter College sociologist of education Catherine Voulgarides, argue that systemic racism – as well as biased interpretations of the behavior of students of color – explains these discrepancies. For example, when compared to students with similar test scores, Black students with disabilities are less likely to be included in the general education classroom than their non-Black peers. To curb this, teachers can take steps toward being more inclusive of students of color with disabilities.

As a Black feminist researcher who focuses on the intersection of race and disability, here are three recommendations I believe can help teachers to better support students of color with disabilities.

1. Inform families of their rights

Federal law requires that schools provide parents and guardians with Procedural Safeguards Notices, a full explanation of all the rights a parent has when their child is referred to or receives special education services. These notices need to be put in writing and explained to families in “language that is easily understandable.”

However, research shows that in many states, Procedural Safeguards Notices are written in ways that are difficult to read. This can make it harder for families, especially immigrant families, to know their rights. Also, families of color report facing greater resistance when making requests for disability services than white families do.

When meeting with families, teachers can take the time to break down any confusing language written in the Procedural Safeguards Notice. This can assure that the families of students of color are fully aware of their options.

For example, families have the right to invite an external advocate to represent their interests during meetings with school representatives. These advocates can speak on behalf of the family and often help resolve disagreements between the schools and families.

Educators can tell families about organizations that serve children with disabilities and help them navigate school systems. The Color of Autism, The Arc and Easterseals are striving to address racial inequities in who has access to advocacy supports. These organizations create culturally responsive resources and connect families of color with scholarships to receive training on how to advocate for themselves.

2. Talk about race and disability

Despite the growing diversity within K-12 classrooms, conversations around race are often left out of special education. This leaves a lack of attention toward the issues that students of color face, like higher suspension rates and lower grades and test scores than their white peers in special education.

When teachers talk about race and disability with their colleagues, it can help reduce implicit biases they may have. Also, dialogue about race and disability can help to reduce negative school interactions with students of color with disabilities.

Arizona State University teacher educator Andrea Weinberg and I developed protocols that encourage educators to talk about race, disability, class and other social identities with each other. These include questions for teachers such as:

Do any of your students of color have an IEP?

Has a student with disabilities or their family shared anything about their cultural background that distinguishes them from their peers?

Are there patterns of students not responding to instruction?

The protocols also encourage educators to consider their own social identities and how those may shape how they interpret students’ behaviors and academic needs:

Who do you collaborate with to help you better understand and respond to students’ diverse needs?

In what ways are students and teachers benefiting from the diversity represented in the classroom?

Educators using these questions in the Southwest, for example, say they help a mostly white teacher workforce understand their role in disrupting inequities. One study participant said, “These things are not addressed, and they’re not talked about among faculty.”

3. Highlight people of color with disabilities in the classroom

Often, classroom content depicts disabled people – especially those of color – as people at the margins of society. For example, in “To Kill a Mockingbird,” Tom Robinson, a Black character with a physical disability, is killed after being falsely accused of a crime. Teachers can incorporate thoughtful examples of disabled people of color in their lesson plans to help students better understand their experiences.

When teaching about Harriet Tubman, educators can mention how she freed enslaved people while coping with the lifelong effects of a head injury. Tubman’s political activism provides a historical example of disabled people of color who helped improve society for all.

Art teachers can highlight Mexican artist Frida Kahlo and how she boldly addressed her physical disabilities in self-portraits. Disabled people’s experiences are frequently shown from the perspective of people without disabilities. In her art, Kahlo displayed herself with bandages and sitting in a wheelchair. Her portraits featured her own reactions to having disabilities.

Physical education teachers can discuss current events, such as recent news about Olympian Simone Biles’s attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and anxiety. Her openness has sparked international conversations about less noticeable disabilities.

Teaching students about the contributions that disabled people of color make to our society emphasizes that neither race nor disability should be equated with inferiority.![]()

Mildred Boveda, Associate Professor of Special Education, Penn State

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.