The Pathology of Mass Shootings

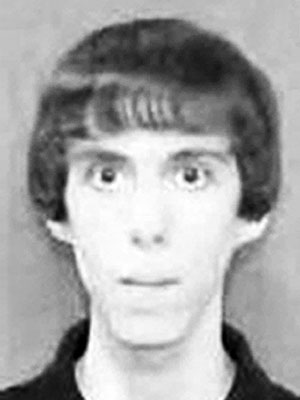

Adam Lanza murdered 20 children and 6 adults at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, CT.

My soul is weary with sorrow; strengthen me according to your word. –Psalm 119:28

When the soul is crushed with the weight of unanswerable questions, how do we begin to bind up our wounds? How many times have we gone through this? How many more can we endure?

We experience such shock each time we hear the news. But at what point do we refuse to dismiss such instances as “random” and “unheard of”? When do as a society begin to take collective responsibly for the lives that have been lost? How many will it take before we examine the “cultural pathology” of mass shooting?

There is a double standard that exists around the explanation of such events. It would not take very many mass shootings in which the perpetrators were black, Muslim, or Latino before we would hear comments about “violent cultures” and the ‘moral bankruptcy‘ of an entire group.

Think that race should have nothing to do with it? Maybe not. Yet when the perpetrator isn’t white, race is routinely injected into the narrative. And no matter how many white male mass-shooter we’ve had, we still live in a society that fervently fears Black men.

Jared Lee Loughner shot former congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords and 18 others in Tucson, AZ. on Jan. 8, 2011. Six of those shot died.

This is the danger of maintaining cultural white male default. We are blind to the ugly aspects of a culture that is perpetually considered ‘normal.’ If these shooters were black men, there would be a collective shaking-of-heads at their ‘inherit violent nature‘. If Latina women were committing mass shootings at a similar rate, the media would certainly be asking what the cause of it might be. But after the Newton shootings, we will see no law enforcement policy changes that will increase the racial profiling of white men.

It is a chilling aspect of white privilege to be able “to kill, maim, commit wanton acts of violence, and to be anti-social (as well as pathological) without having your actions reflect on your own racial group” (Chauncey DeVega). Time and again, the white men who commit these mass shooting are framed as “lone wolves” and “outliers,” with little examination or reflection on a broader cultural responsibility.

On July 20, 2012, James Eagan Holmes shot multiple guns into the audience at a midnight screening of ‘The Dark Knight Rises,’ killing 12 people and injuring 58.

Abagond also notes the trend:

“When white people do something bad it is due to circumstances, a bad upbringing, a psychological disorder or something. Because, apart from a few bad apples, white people are Basically Good. Everyone knows it. But when black people do something bad it is because they were born that way.”

When the shooter is white, we dig into school and psychiatric records in search for explanations as to why someone so “normal” would do such a thing. The shooter is often perceived as the quite, unremarkable “boy next door” that no on ever dreamed would suddenly snap.

Charles Carl Roberts murdered five girls and injured five others at an Amish school in Lancaster County, PA., on Oct. 2, 2006.

When violence is perpetrated by a person of color, we are quicker to be satisfied with broad explanations of terrorism, religion, or turf wars. Indeed, “after Maj. Nidal Hasan carried out the Fort Hood shootings, his Muslim faith became all the public needed to know about his motive.” The news media routinely “pathologize people of color as naturally criminal and violent.” Urban is used as shorthand for immorality.

As sensationalized as inner-city violence is, mass shootings of strangers in public settings like schools and shopping malls are virtually non-existent in urban neighborhoods. And despite gun-blazing stereotypes, the majority of people of color are pro-gun control, in stark contrast to the white voting public.

Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold committed the Columbine High School massacre on April 20, 1999, killing 13 people and injuring 24.

Finally, the understandable horror that is felt after each mass shooting is in stark contrast to the silence and apathy with regard to the children that are dying on the streets everyday. There are daily cries for change and regulation coming from the mouths of mourning mothers that are never heard. The shock expressed after the events like those in Newton subtly sends the message that “this shouldn’t happen here, in our idyllic white suburban community. We’re not like those neighborhoods where you expect random violence.” These attitudes are reflected in the difference in public attention span depending on the race of the victim, whether it’s a shooting at a Sikh temple, or a missing child report.

When white is seen as the default, any deviant behavior can be excused as the exception to the rule. Conversely, when we limit our interactions with those of other races, we are forced to rely on heuristics to generalize about the “other.” If Adam Lanza were black, it would reaffirm stereotypes of a violent culture. If he were Muslim, the shooting would be a “clear act of terrorism.” But as a white male, he is characterized as a disturbed individual, wholly distinct from the race and culture to which he belongs.