by Allen Reynolds, UrbanFaith Editor | Feb 20, 2023 | Black History, Commentary, Headline News, Magazine, Social Justice |

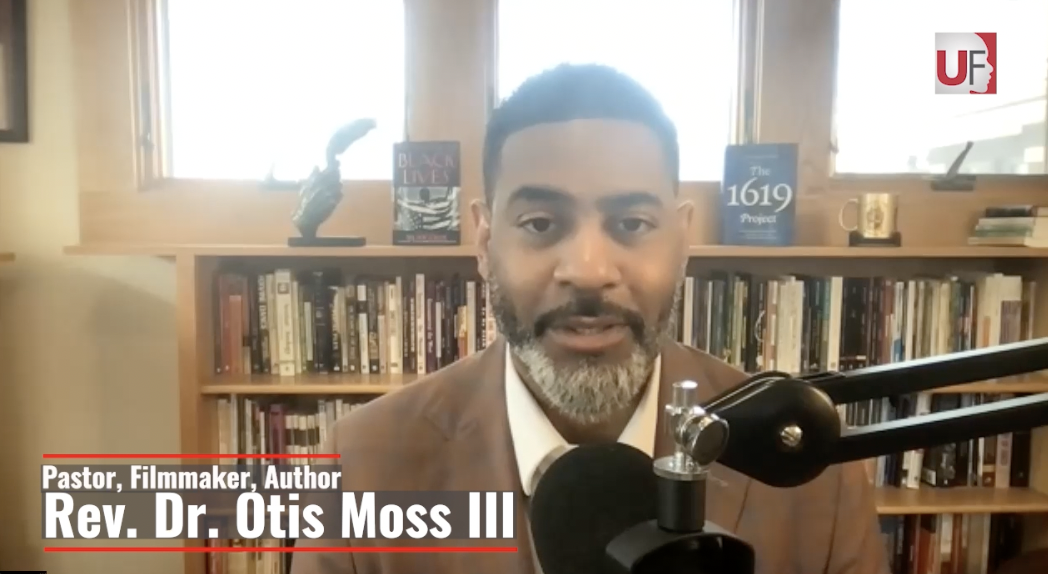

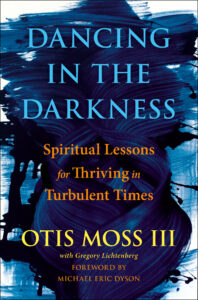

Rev. Dr. Otis Moss III is one of the most prolific prophetic voices of our generation. He is the Senior Pastor of Trinity United Church of Christ in Chicago, IL and his new book Dancing in the Darkness gives practical wisdom to face the darkness in our lives with prophetic hope. UrbanFaith editor Allen Reynolds sat down with his fellow HBCU and Yale alumnus, the one and only Rev. Moss to discuss his new book Dancing in the Darkness: Spiritual Lessons for Thriving in Turbulent Times. You can find the book everywhere books are sold and more about the book is below.

Rev. Moss serves as Senior Pastor of Trinity United Church of Christ which was the home church of President Barack and Michelle Obama. He has won multiple awards for his short film Otis’ Dream about his grandfather’s fight to vote in the United States. His parents were on the front line of the Civil Rights Movement, and he has been at the forefront of the fight for justice and civil rights in the 21st century. He calls himself a blues man committed to uniting love and justice in the tradition of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. More about the book is below.

Once again, as Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. first observed in the 1960s, it is midnight in America—a dark time of division and anxiety, with threats of violence looming in the shadows. In 2008, the Trinity United Church in Chicago received threats when one of its parishioners, Senator Barack Obama, ran for president. “We’re going to kill you” rang in Reverend Otis Moss’s ears when he suddenly heard a noise in the middle of the night. He grabbed a baseball bat to confront the intruder in his home. When he opened the door to his daughter’s room, he found that the source of the noise was his own little girl, dancing. She was simply practicing for her ballet recital.

In that moment, Pastor Moss saw that the real intruder was within him. Caught in a cycle of worry and anger, he had allowed the darkness inside. But seeing his daughter evoked Psalm 30: “You have turned my mourning into dancing.” He set out to write the sermon that became this inspiring and transformative book.

Dancing in the Darkness is a life-affirming guide to the practical, political, and spiritual challenges of our day. Drawing on the teachings of Dr. King, Howard Thurman, sacred scripture, southern wisdom, global spiritual traditions, Black culture, and his own personal experiences, Dr. Moss instructs you on how to practice spiritual resistance by combining justice and love. This collection helps us tap the spiritual reserves we all possess but too often overlook, so we can slay our personal demon, confront our civic challenges, and reach our highest goals.

by Kathryn Post, RNS | Apr 21, 2022 | Commentary, Headline News, Social Justice |

(RNS) — Pastors in Grand Rapids, Michigan, are taking action as the city reels in the aftermath of the fatal shooting of 26-year-old Patrick Lyoya by a Grand Rapids police officer on April 4. Video footage of the shooting was released on Wednesday (April 13), sparking protests outside the city’s police department.

Lyoya, who is Black, was pulled over last week for a mismatched license plate. Video footage shows a white officer shooting Lyoya in the head after a brief scuffle. Lyoya and his family arrived from the Democratic Republic of the Congo in 2014 as refugees, and he leaves behind his parents, two young daughters and five siblings.

In the days since Lyoya’s death, a group of Black pastors in Grand Rapids, called the Black Clergy Coalition, has been organizing community events to promote dialogue, healing and justice.

“We think that our faith perspective is critical in this hour, to not just discuss policy change, which is necessary, but to also discuss the spiritual and faith dynamic,” said Pastor Jathan K. Austin of Bethel Empowerment Church in Grand Rapids. “We must continue to keep our trust in the Father so that people don’t lose trust in this time because of the heartache, the pain.”

On Sunday (April 10), the group helped organize a forum for community discussion in response to Lyoya’s death. The discussion took place at Renaissance Church of God in Christ in Grand Rapids — the location was intentional, according to the church’s senior pastor, Bishop Dennis J. McMurray, who noted the wider church’s historic role in guiding civil rights movements and said the Black Clergy Coalition is drawing on that legacy.

“It was unreal, the level of cooperative dialogue and understanding that took place,” McMurray told Religion News Service. “If these conversations would have started almost anywhere else, the volatility that could be associated to something as devastating as what we’re facing could have been a bomb that goes off that would cause so many other issues.”

The group also helped host a Thursday press conference at the Renaissance Church of God in Christ and a noon Good Friday service at the church, where they took up a collection for the Lyoya family.

The Rev. Khary Bridgewater, who lives in Grand Rapids, said the city’s racial and religious landscape informs how local leaders are responding to Lyoya’s death. Grand Rapids has a population that’s over 65% white and about 18% Black. It’s also the headquarters for the Christian Reformed Church, a small, historically Dutch Reformed denomination, and is home to over 40 CRC churches. According to Bridgewater, leaders shaped by the CRC’s reformed theology are often more likely to advocate for change within existing systems.

According to Bridgewater, “It’s very hard for most CRC churches to look at a system and say, ‘This is wrong, we’re going to act as activists to push the system into a different state.’ They’re more inclined to say, ‘Hey, let’s sit down and have a conversation with the leaders and try to do things differently.’” Bridgewater says this theology can bump up against the Black church’s prophetic tradition of change-making. For this reason, he said, Christian groups in Grand Rapids need to have theological discussions around topics like justice and citizenship.

Nik Smith, a Grand Rapids activist and member of Defund the GRPD, agrees the city’s religious culture is shaping local leaders’ responses.

“The nonprofits are run by Christian folk who are just waiting for Jesus to come, not realizing not only was he here already, but he’s given us things to live by,” said Smith. “So we have to be seeking justice actively in our community. We can’t just say, let’s pray. Prayer is not going to bring Patrick back.”

Smith has been involved in Defund the GRPD since 2020, when the coalition first began advocating for reducing the police budget and refunding over-policed communities. Though Smith doesn’t identify as a Christian as strongly as she once did, she believes the Bible highlights the consequences of earthly authorities wielding too much power and the importance of working to make the world a better place. For Smith, defunding the Grand Rapids Police Department is part of securing a better future.

For years, the city’s police department has been criticized for racial profiling and for drawing guns on Black children. Joseph D. Jones, who is a city commissioner and pastor, told Religion News Service he wants to address police and community relations by looking at “root causes” of socio-economic inequality and other disparities while also addressing training for officers.

“I do believe in the absolute power of prayer,” Jones added. “I’m asking those who do pray … to pray for the family of Patrick, to pray for our city, to pray that angels are encamped around our city to protect our city and to pray that God restore and change the hearts of those who desire to engage in anything that is seen as evil in our country and our world,” Jones said.

Austin of Bethel Empowerment Church said the Black Clergy Coalition has long been advocating for police reform and specifically wants to see better diversity and culture training for officers and changes in how the department responds to police shootings.

“I am going to allow the wheels of justice to roll, and we pray that they roll properly,” said McMurray, who is also part of the coalition. “We are working, but we’re also watching.”

READ THIS STORY AT RELIGIONNEWS.COM

by Fredrick Nzwili, RNS | Sep 23, 2021 | Headline News |

Kenya, in red, located in eastern Africa. Map courtesy of Creative Commons

NAIROBI, Kenya (RNS) — Some churches in Kenya have barred politicians from addressing their congregations, saying campaigning during services disrespects the sanctity of worship.

The national Anglican, Presbyterian and Roman Catholic churches have all issued bans, as many of the politicians begin early stumping for next year’s general elections. The Methodist Church, however, is keeping the church doors open for all.

The Rev. Joseph Ntombura, presiding bishop of the Methodist Church in Kenya, has said his church is not dissenting from the effort but is taking a different approach. The bishop said shutting the doors to politicians would mean discriminating against some of its members.

“The church is for all people,” Ntombura told Religion News Service in a telephone interview. “Human beings are political, so there is nothing wrong with inviting the politicians in church.”

According to the bishop, congregations need to hear the views of politicians on issues of national interest, such as the sharing of resources. In the past, Ntombura said, the church has invited other experts to speak to congregations on important matters, and politicians are no different.

“Some of the politicians are our pastors,” said Ntombura.

The Rev. Joseph Ntombura, with microphone, presiding Bishop of the Methodist Church in Kenya, prays over former Nairobi Governor Evans Kidero, left, in Nov. 2015. RNS photo by Fredrick Nzwili

Kenya is about 85% Christian. About 33% of that group are Protestants and 20.6% are Catholic. The rest belong to evangelical, Pentecostal and African denominations. Muslims make up 11% of the population.

In issuing the bans on politicking in church, denominations have said they feared that church services would become campaign rallies and that candidates would use language bordering on hate speech in an attempt to win votes or sway the views of congregations. In the past, politicians hijacked church services to sell their agendas or criticize their opponents. Some have appeared in the churches with huge sums of money as offerings or as funds for church projects.

The no-politicking effort gained momentum this month when Archbishop Jackson Ole Sapit, the Anglican primate of Kenya, announced his church’s ban.

“Everyone is welcome in the churches, but we have the pews and the pulpit,” said Ole Sapit on Sept. 12, during the ordination of Kenya’s first Anglican woman bishop. “The pulpit is for the clergy and the pews for everyone who comes to worship.”

On Sept. 15, the Roman Catholic bishops said their places of worship and liturgy were sacred and were not political arenas. They urged politicians to attend Mass just like any other worshippers.

Analysts say the churches are seeking to reclaim their position as “honest arbitrators” in a country where elections often generate violent conflicts.

The most deadly came in December 2007 and January 2008, when two months of ethnic fighting left at least 1,000 people dead and more than 600,000 displaced from their homes. Among them, 30 people, mainly ethnic Kikuyu, Kenya’s largest tribe, were burnt alive in an Assemblies of God church in Kiambaa Village in Eldoret.

Henry Njagi, program and information manager at the National Council of Churches of Kenya, said resistance to church guidelines on political speech risks a repeat of the events of 2008.

“When things went wrong, they turned around and accused the church of being silent and abandoning Kenyans,” said Njagi. “So right now is a call on political actors, aspirants and other stakeholders to listen to the church … and stop toxic politicking.”

Though the politicians have not been as present at mosques, Muslim leaders say they are supporting the ban on toxic politicking in the churches.

“I support the Christian leaders. Such a ban is long overdue,” said Sheikh Hassan Ole Naado, national chairman of the Supreme Council of Kenya Muslims.

He added that Muslims were not facing the issue at the moment.

“When you go to a place of worship, you know what you are supposed to do. They are taking advantage of people who are gathered for worship. It should not happen in the first place,” said Ole Naado.

by Yonat Shimron, RNS | May 20, 2021 | Headline News |

Originally published May 12, 2021

(RNS) — Violence between Gaza and Israel intensified this week to levels not seen for years, with Hamas shooting hundreds of rockets toward the Tel Aviv metropolitan area and Israel retaliating with heavy strikes on Hamas targets in the Gaza Strip.

The buildup to the current conflagration — some are already calling it a new “intifada” or “uprising” — began several weeks ago in a Jerusalem neighborhood near the Old City, close to the Al-Aqsa Mosque, one of Islam’s holiest sites for more than 1,200 years.

While Muslims pray at Al-Aqsa year-round, the mosque attracts even more worshippers during Ramadan. Wednesday (May 12) marked the end of Ramadan and the start of Eid al-Fitr, a joyous time for millions of Muslims concluding a monthlong fast.

There’s no doubt that the most extreme Jewish nationalists would like Israel to recapture the Al-Aqsa Mosque because they say it sits on top of the ruins of the ancient Jewish Temple, the only remainder of which is the Western Wall.

But except for the setting of the conflict, faith is only tangentially related to the violence. Here’s a quick explainer on the conflict of the past few days, and what, if any, role religion plays.

Why did Israeli police raid the Al-Aqsa Mosque to begin with?

The Israeli government said the police responded after the Palestinians started throwing stones at them. Palestinians say the fighting really began when police entered the mosque compound on May 10 and started firing rubber-tipped bullets and stun grenades. More than 330 Palestinians were wounded. Israel said 21 of its officers were, too.

But the underlying tensions may have more to do with a set of clashes in the larger east Jerusalem area, which was captured by Israel in the 1967 Six-Day War and is home to about 350,000 Palestinians.

For weeks prior to the mosque violence, Palestinians had been protesting the threatened eviction of Palestinian families from the Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood of east Jerusalem. At night they would clash with police and far-right Jewish settlers.

Those clashes are in turn part of a long legal battle over who owns the property. Some Palestinians were relocated to Sheikh Jarrah by the Jordanian government in the 1950s after fleeing their homes during Israel’s War of Independence in 1948.

On May 10, the Israeli Supreme Court was set to decide whether to uphold the eviction of six families from the Sheikh Jarrah neighborhood in favor of Jewish settlers. The court has since postponed the ruling.

So this is a land dispute?

On a large scale, yes. In Sheikh Jarrah, in particular, the dispute originates in the 19th century, when Jews living abroad began returning to what is now Israel and buying properties from Palestinians who lived there. The Jordanians took over the land between 1948 and 1967. Israelis are now claiming it’s theirs again.

The dispute in Sheikh Jarrah takes on political overtones because the neighborhood is part of east Jerusalem, which Palestinians want name as the capital of a future Palestinian state encompassing the West Bank and Gaza. Many Israelis, regardless of their views about a Palestinian state, believe Jerusalem must remain “a Jewish capital for the Jewish people,” and under Israeli control.

What’s Hamas got to do with it?

The clashes between Israel and Palestinians in Jerusalem have united Palestinians far and wide, as have the larger disputes over their displacement and disenfranchisement by Israel. Hamas, the Islamist militant group that controls the Gaza Strip, located about 60 miles south of Jerusalem, sees itself as a defender of Palestinians.

Hamas is at root an Islamic organization born from members of the Muslim Brotherhood, and so it also cares deeply about the Al-Asqa Mosque, which Muslims call the Noble Sanctuary.

On May 12, Israel assassinated several Hamas commanders in retaliation for the barrage of rockets on Tel Aviv, Ashkelon and Israel’s main international airport in the city of Lod.

What role does Judaism or Islam play in this?

At heart, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is a dispute over land. But religion is often the proxy for those disputes, pitting two different ethnicities and religions. Little wonder those tensions tend to flare around religious holidays, both Jewish and Muslim.

But Hamas’ main goal is not war with Judaism, but rather with Israel, which is occupying land it believes is inherently Palestinian.

As Hamas has become more emboldened over the years, so too, have Jewish nationalists. On Monday, May 10, which was Jerusalem Day, a national holiday celebrating the unification of Jerusalem, Jewish nationalists marched through the Old City of Jerusalem, including the Muslim Quarter, in a display that provoked and angered many Palestinians.

As often happens, the exclusive claims to parts of the holy city often turn deadly.

by Alex Leeds Matthews | Sep 18, 2018 | Headline News, Social Justice |

Asale Chandler holds a picture of her son, Yalani Chinyamurindi, who was murdered at age 19. Now, Chandler is a running for the Board of Supervisors in San Francisco. (Alex Leeds Matthews/California Healthline)

SACRAMENTO, Calif. — More than three years have passed since Asale Chandler’s teenage son was murdered in San Francisco. But Chandler said it feels as though it has been only three days.

The anguish doesn’t get better, said Chandler, a 55-year-old community activist from San Francisco at a recent rally. “It gets worse.”

Chandler’s 19-year-old son, Yalani Chinyamurindi, was one of four young black men who were shot and killed in January 2015 while sitting in a Honda Civic in the city’s Hayes Valley neighborhood. One man has been arrested in connection with the shooting.

Chandler prayed, protested and communed with other mothers — and brothers, sisters, aunts and uncles — who have lost their loved ones to violence.

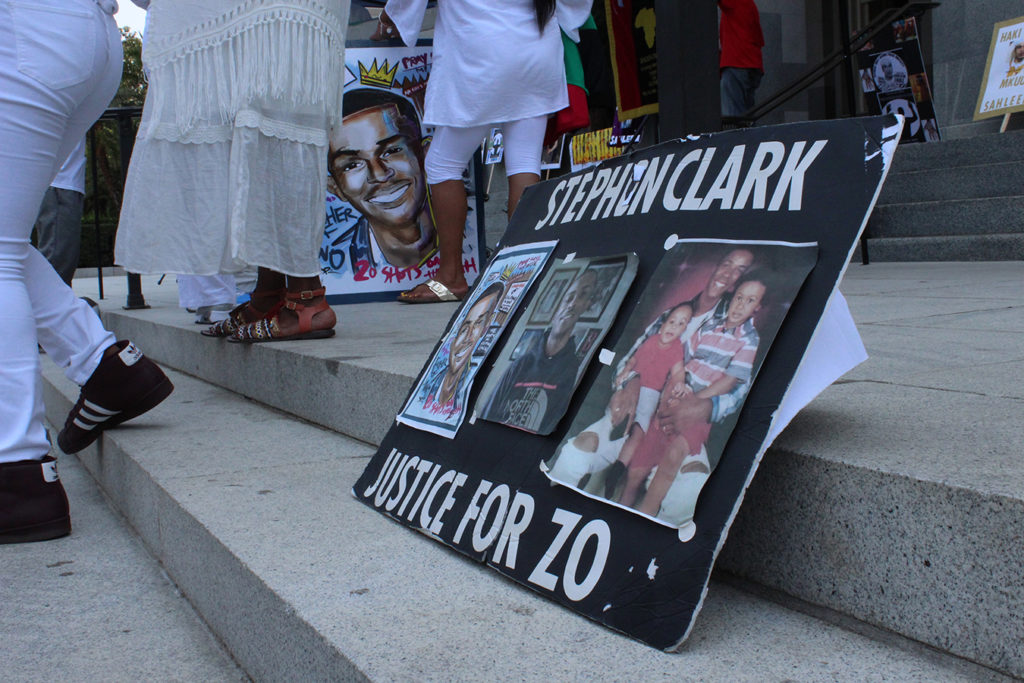

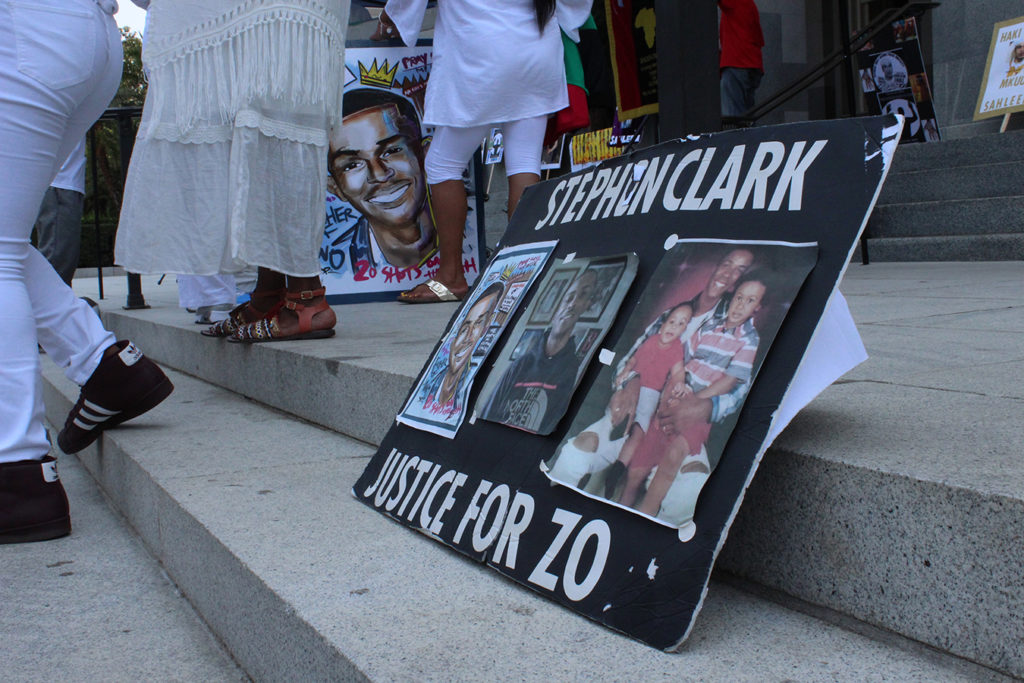

The “Mothers Fight Back!” rally came amid ongoing unrest over the police shootings of unarmed black men, including Stephon Clark, who was killed in his grandmother’s backyard in Sacramento in March. His death sparked large-scale protests that blocked traffic and disrupted Sacramento Kings basketball games.

But attendees of the rally noted they were speaking out against violence of all kinds, not just police brutality. They said they took to the Capitol steps to grab the attention of lawmakers and journalists.

A poster commemorating Stephon Clark, who was killed by Sacramento Police in March, sits on the Capitol’s steps during the Mothers Fight Back! rally. (Alex Leeds Matthews/California Healthline)

A few, like Chandler, are running for public office. Others participated to support their loved ones and join in solidarity with other mothers.

“You do want to connect to a mother or a father who’s been through it,” Chandler said. She hasn’t found solace through therapy or medication, but said being around other mothers whose lives were also transformed by violence is “the true medicine.”

The rally was passionate, but it wasn’t as pugnacious as its name might suggest. The moms came bearing snacks, handcrafted posters and children’s books. They sang and said prayers.

Participants said they are facing a dire mental health crisis fueled by violence, trauma and uncertainty.

“It’s traumatic for all of us. … We’re scared to death. We don’t know what to do, we don’t know how to act,” said Leia Schenk, 40, a social services worker in Sacramento, who is close with Sahleem Tindle’s family. Tindle was shot and killed by BART police near the West Oakland BART station in January.

Asale Chandler’s son was murdered more than three years ago in San Francisco. At a recent rally, the community activist participated in a Hebrew “mother’s prayer” at the Mothers Fight Back! rally at the Capitol. (Alex Leeds Matthews/California Healthline)

Schenk said she struggles with the emotional fallout from the violence and fears for her children, particularly her two black sons. “It’s a helluva way to live,” she said.

Black children die from gun-related homicides at a rate nearly 10 times higher than that of white children, according to a 2017 study in the American Academy of Pediatrics. Another study published a few weeks ago showed that black men are at risk of being killed by police at a rate about triple that of white men.

The statistical differences are important, said Chet Hewitt, president and CEO of the Sierra Health Foundation, which awards grants to reduce health disparities.

However, the numbers don’t reveal the mental and physical pain that afflicts victims and their communities contending with violence, said Hewitt, who did not attend the rally.

“You are constantly on high alert, and you are constantly in a state of mourning,” said Cat Brooks, an Oakland mayoral candidate and a co-founder of the Anti Police-Terror Project.

Brooks, who has a 12-year-old daughter, attended the gathering to address the struggle many black parents encounter trying to protect their children from violence.

“Because there is no rhyme or reason to our people getting killed, that means there’s no one to tactically figure out how to avoid it,” said Brooks, 41. “We teach our children everything we can about how to stay alive.”

A poster commemorating Stephon Clark, who was killed by Sacramento police in March, sits on the Capitol’s steps during the Mothers Fight Back! rally.

That trauma, fear and uncertainty has measurable effects on health.

According to the American Psychological Association, more than 25 percent of African-American youths exposed to violence are considered at risk for post-traumatic stress disorder. Symptoms of PTSD include anxiety, flashbacks and difficulty sleeping.

Community cohesion can help people heal from acts of violence, but violence can also erode that sense of togetherness, said Flo Cofer, director of state policy for Public Health Advocates, a nonprofit organization that works to address health disparities.

Many of the communities most affected by violence also face other physical and social challenges like poverty, hunger and educational obstacles, she said.

“That’s part of the reason why the violence is so devastating. This is happening in a place where trauma is the air they breathe,” Cofer said in a phone interview.

At the rally, the low-key gathering of approximately 50 people consisted mainly of women and children. Moms parked strollers under a tent while their former occupants munched on crackers or toddled on the Capitol steps.

As one little girl, dressed in flowery overalls and shimmery sandals, danced to the “Circle of Life” song, adults and older children, dressed in white, surrounded her, clapping to the beat.

When the mothers gathered for a Hebrew “mother’s prayer,” Chandler stood near the front with her arms stretched above her head.

She is running for the Board of Supervisors in San Francisco to address the violence in her Bayview-Hunters Point neighborhood. “I’ve seen nothing but yellow tape, and it messed me up so badly,” she said.

Yolanda Banks Reed led the prayer.

Banks Reed’s son was the young man who was killed nearly seven months ago near the BART station. She said she knows the mental toll will be lifelong.

“It’s a life sentence for a mother,” she said. “A mother should not lose her children.”

Article published courtesy of California Healthline